IN THE GREEN SPACE

Bridging

Spiritual Direction

and

Relational

Psychotherapy

through

Spontaneous Artwork(1)

by

Jacqueline

Fehlner

This is a digest of a the paper written by Jacqueline Fehlner.

At the time of writing, the author was enrolled in a course

at the

Institute of Christian Studies, Toronto.

Her studies in Relational Psychotherapy and its relationship to faith along with a more Protestant perspective was the context for the following reflections.

These studies have helped her to be more sensitive to the needs and experiences

of the many clients who come to her from diverse backgrounds.

Invitation to Service

Over these past years I have worked as an Art Therapist and also as a Spiritual Director. At times I exercised these roles separately; at other times together. When asked: "How do you distinguish psychotherapy from spiritual direction?" my response has been, "By the intention and statement of the person who comes to see me."

Long before my spiritual direction ministry I worked in pastoral care and in art therapy. Even then I discovered that, for healing to take place, God had to be part of the picture -- at the least in my life, as the helper in the pastoral-care or art-therapy helping relationship. Otherwise, hope fades and frustration and despair creep in; perspective is lost and energy is placed on immediate solutions or goals; the passion for life erodes into predictable routines, which sap the spirit and interfere with a new vision for self and others.(2)

Psychotherapy is about relationships -- relationships with the self and others and how one has connected with the past and how one continues to connect, disconnect and reconnect with others and the authentic self.

Spiritual direction is also about relationships -- relationships with self, with God, and with God's people. It is about how those connections are made and nurtured by the word of God and how disconnections may occur and be reconciled through prayer. It is only very recently that psychiatrists and psychotherapists have been willing to admit that there is a place for God in their work with clients.(3) Hungry for something more in their life or aware that their prayer life has become dry or so routine that it has little meaning or nourishment for them, some people today are open to searching for an adult faith rather than stay with their childhood beliefs. (4)

A psychology which is open to spirituality gives its adherents permission to be their authentic selves and openly draw strength and hope from the deepest roots of their faith. Perhaps, The Beautiful Risk: A Spiritual Psychology of Loving and Being Loved by James Olthuis will alter that fear for some who have avoided seeking help in the past lest they be shunned and stigmatized by their family or Church community. This book certainly will give permission to those people open to a postmodern worldview to approach therapy from a different stance. It also gives an invitation and challenge. For therapists, it is to allow one's faith experience into the healing process. For their clients it is to bring God into the picture and re-enter the scene with Jesus as part of the healing journey to new hope and new life.

II. Explanation of Technical Words.

The term "spiritual direction" and the words related to it are not understood in the same way by everyone. Hence, at this point I will clarify my terminology. In its broadest sense, "Spirituality is an entrance into solitude and reflection where one is called into relationship with Someone greater than oneself in order to become unconditionally loving and free."(5) As a practising Catholic Christian I understand that that Someone is God and specifically, Jesus, who has shown the way into unconditional love and freedom. Prayer is what happens in the entrance into solitude and reflection. It is in prayer that the relationship with God, others, and self develops, grows and is enhanced. Prayer is the most intimate of communications.

Spiritual direction is an opportunity to meet on a regular basis with a person of faith and prayer to explore one's relationship with God and God's people and to deepen one's prayer life. It is present and future oriented, although it does not ignore the person's personal, social and faith history. It is a journey one takes in faith and love and trust. The person who seeks out such a journey (the directee) meets with the director (guide) to discuss discoveries and challenges in the directee's prayer and in their experience of relationship with God and his/her community. Through reflection and prayer, one becomes aware of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit and how one's life reflects the living out of the Gospel in union with Jesus. For those facing a change in life direction, spiritual direction can aid in the discernment process to follow Jesus in the new direction in which that person is being called. Spiritual direction is usually given on an individual basis.

What is a Spiritual Director or Spiritual Guide?

A Spiritual Director is a person who has a deep, personal relationship with God through prayer and community, and is open to the working of the Holy Spirit within the directee as well as oneself. A Spiritual Director listens attentively in a non-judgmental manner to the relational story and prayer of the directee and may give suggestions for the times of prayer and feedback when appropriate. The role of a Spiritual Director in spiritual direction is not telling a person what they should believe, or how they should pray or worship, but one of affirmation of the person's growing relationship with God. Depending on the needs of the person who seeks spiritual direction, the director-directee relationship may resemble the role that a therapist has with the person who comes to him/her for help. A Spiritual Director is a catalyst through whom the Spirit works for the good of the other. At times, the Spiritual Director or the therapist is a teacher-facilitator, a mid-wife, a companion in prayer or a sojourner.

What is Art Therapy?

Art Therapy is a form of psychotherapy that uses a non-verbal approach

-- spontaneous art -- which enables a person to express him/herself in

a non-threatening way to reconcile emotional conflict and to promote personal,

mental and spiritual growth. It taps the creative process by exploring

and experimenting with simple art materials and leads to creating alternatives

for oneself. This process can be facilitated in both individual and/or

small group settings. Although its pioneers were steeped in Freudian and

Jungian psychodynamic theories, Art Therapy can be successfully practised

working from many theoretical bases.

III. Hospitality, Creativity, Prayer

Our team was formed after Sr. Michael and I shared prayer and faith for several years. Spontaneous artwork was a part of this journey. There was a desire to share and pass on what we were learning and receiving. Out of an individual and communal discernment process came awareness and a plan for how our different gifts and experiences could be brought together in service to God's people within the setting of St. Michael House.(7) Sr Michael and I understand what we do as facilitation and spiritual companioning. During the times of retreat, particularly as co-facilitators, we trust that the Spirit gives guiding insight to one's companion-director as well as to the persons on retreat -- the retreatants. Neither of us is an "expert" who has "made it." Spiritual Directors are "subject to the same hurts and temptations. Loneliness, self-contempt, moral ambiguity attack them as much as anyone else."(6) Though we facilitate the process in others we are also invited by the Spirit to grow in love and understanding. That is part of the gift that we help to pass on. Through the long paths of our own personal psychotherapeutic work and spiritual direction, we have come to know and love our own story and have experienced the healing hand of our Creator. God continues to shape and reshape us as the potter reshaped the clay (Jeremiah 18:1-6).

Spiritual companioning is very much like an Emmaus walk in which Jesus listened, was a companion on the journey, and shared his understanding. Other times it is much like the Good Shepherd who tends and feeds those in his care. As a Spiritual Director-companion, one is an instrument/catalyst through which the Spirit works and stirs the heart of the person who comes for ongoing guidance or for several days of intensive and structured meditative prayer.

Place of prayer

Our prayer and work styles are rooted strongly in Benedictine Spirituality, with its flow from worship into work, play, and community; and in Ignatian Spirituality with its focus on being a contemplative in action. Both spiritualities invite us to become quiet for parts of the day and enter into a stillpoint. The day is hemmed in with prayer and reflection. We use a variety of forms of prayer to understand better their effect. Art was a form that spoke loudly to us, and that is why we decided to incorporate it into our retreat programs. One of the exercises that we did individually and shared was Kathleen Fischer's, Our Legacy: The Communion of Saints exercise,(8) which can be found in Appendix B. This prayer exercise invites the participant to find connections with others, and aware of them, to celebrate them or begin a reconciling process.

Rationale behind our ministry

Personal growth and spiritual development is ever ongoing -- visible and vibrant at times and very subtle and slow at others, a mix of pain, suffering and joy. Opportunities for growth and development come in times of crisis, if one is open to reflecting upon and learning from one's experiences. To do so, the person may need a support community, which may have either a psychological or spiritual focus or a combination of the two.

Victor Frankl writes in Man's Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy: "Emotion which is suffering, ceases to be suffering as soon as we form a clear and precise picture of it."(9) Some people have no words or only limited words for what has happened to them. They need a visual voice because their verbal voice was taken away from them.

Art Therapy is one way to help a person form and express a "clear and precise picture of it" whatever the "it" may be that is sucking the person into a downward spiral and blocking his/her ability to be present, to learn, and to become what God calls him/her to become. There are three parts to art therapy: the person, the process, and the art product. In relational psychotherapy and spiritual direction there are parallel aspects: 1) the relationship, 2) the risk-taking and working through, and 3) the personal growth and spiritual development which may lead to healing of mind, body and relationships as connections are either re-established or created for the first time.

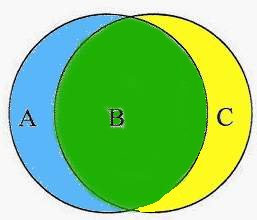

There are some aspects of spiritual direction and psychotherapy that have the same focus; and hence, there is some overlap. In the early stages, it can seem that a spiritual guide's activities are much like that of a therapist. Here are three diagrams(10) that are very helpful in understanding the overlap between psychotherapy and spiritual direction. First, a Venn diagram(11) to show the overlap in the early stages of growth and recovery.

In this diagram, blue (A) represents the spiritual direction aspect and yellow (C) represents the psychotherapy part. When blue and yellow are combined in the paint palette, green (B) is the new colour that is made. Since we often work with people who are in the beginning stages of their adult faith journey and also recovering the life that God meant them to have, we often work in the green space: bridging spiritual direction and art therapy.

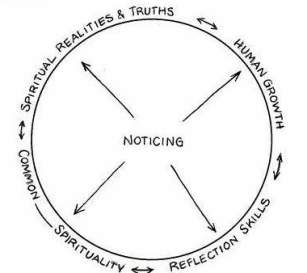

Then there is diagram 2 -- a wheel with its spokes:(12)

This

second diagram demonstrates the movement and areas of concern that a spiritual

guide hopes the person will begin to notice: spiritual realities and truths,

human growth, reflection skills, and common (faith tradition) spirituality.

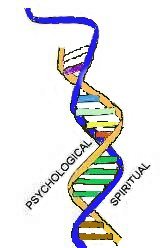

A third diagram, the double helix(13) shows the bridging that is done between the psychological and the spiritual. In this third diagram, orange signifies one's psychological development. Blue signifies one's spiritual development.

In the first bridging, brown is symbolic of the grounding that takes place as director and directee (therapist and client) come together to work. In the second bridging, green is symbolic of new awareness gained and the growth that is happening as they journey together. In the third bridging, the colours correspond to different chakra points and the types of issues brought to psychotherapy and into prayer and a faith journey. They are: red -- the physical, yellow -- the emotional, green -- the heart, blue -- the mind, and purple -- the spirit.

In many situations, the psychotherapeutic counsellor complements the work of the Spiritual Director and vice versa. Spiritual direction is relationally based. It leads toward healing of meaning while psychotherapy works toward healing of integration.

Healing of meaning is finding the self engaged in a relationship with God through one's encounter with the Gospel story of Jesus. Healing of meaning has more to do with learning to tell one's own life stories and to re-establish them in the light of the gospel, thus opening oneself for the acceptance of mystery into one's life through the influence and companionship of God's Spirit.(14)In the healing for integration, the psychotherapeutic counsellor:

... helps the client to attend first to her/his present life experience and, then, to work backwards to relieve the blockages to human growth…. If the psychotherapeutic counsellor helps the client to consider the future and move forward with good decisions, it is be way of presenting options and strategies for coping with life's hurdles and transitions. The skilled focus of the psychotherapeutic counsellor is primarily on the client's self and on the conflicts within the self in order that the client will be empowered to cope more effectively in her/his circumstances of life. If the focus is on the person in relationship with other persons, it is through the therapist's dealing with the client's self.(15)The difference between psychotherapeutic counsellor and the Spiritual Director is the focus from which they work. The Spiritual Director attends to the directee's present experiences of prayer and that which surfaces out of the dynamic of prayer. The skilled focus of the Spiritual Director is primarily on the directee in her experiential relationship to other persons; that is, to God as manifested through the persons of the Trinity who are involved in our world. If the spiritual director's focus is on the directee's self and her conflicts in coping, it is through the Spiritual Director's attempt to deal with the directee's relationship to God.(16)

The reality is that as an Art Therapist/Spiritual Director I may work with a person referred to me from either side of what can be a fine line in this postmodern world. It really does depend on the stated intention of the person seeking help.(17)

IV.

Team Formation

Open

and Present to Mystery

Debra Linesch (29) challenged her colleagues in Art Therapy to become more focused in their profession by asking: "What psychological theories have formed you and your approach to your work in art therapy? Whose theory is the basis for your work and interpretation?" This question can be expanded to include other types of formation. For me, it is not psychological theory that has formed me so much as it is the Spiritual Foundation that I have received throughout my life as a Catholic Christian with its emphasis on living a sacramental life.(19) It is the spiritual works, teachings and lives of people like Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross, Benedict and Francis of Assisi, Ignatius Loyola and Julian of Norwich, that have influenced me and that have been integrated into my life and work style. All of the above mentioned were people who called for reforms within the Christian Church during the time in which they lived.(20) Long before the science of psychology, these people were very much attuned to the working of the psyche with the spirit. What they advocated as a way of being in the world was very therapeutic for many through the ages to today. The reader will find an updated reflection on the gifts gleaned from them in Appendix C.

What has truly formed me personally and professionally has been the people who have reflected the face of Christ and my desire to grow in relationship with Jesus and all God's people. As this relationship is integral to my life and who I am, it has become a part of my work as a spiritual director, Art Therapist and educator. It is also a part of my workplace be it the retreat house, the art studio or the classroom. My team colleague, Sister Michael, received a deep and penetrating development through her formation in Religious life. In terms of style, she is very much Rogerian in the way she interacts with retreatants. I, too, use that style with retreatants and with those who come explicitly for Art Therapy. In addition, my approach to viewing artwork is Jungian. Both Rogers and Jung incorporated an attitude that was very Christian into their theory and methods. As well, our ministry harmonizes with the approach of relational pyschotherapy.

We both follow some of the tradition of Ignatius of Loyola, the 16th century Spaniard who breathed the same mystical tradition as Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross. Ignatius spent a year living in a cave at Manresa, reflecting on his lifestyle as a soldier and on his relationship with God, his family, and other significant relationships. His approach to praying over and dealing with the Scriptures was something he called "contemplation" in his Spiritual Exercises. In our time we would name it: "the use of the active imagination."(21) Through this method, Ignatius would put himself into the Gospel passage and become a part of the story, allowing each aspect to touch him: imagining, feeling and thinking what that person, animal, or thing might feel, think, act or react in interaction with Jesus. He then stood back and reflected upon his prayer experience of when he had put himself into the picture.

Detaching from the picture or the experience, Ignatius then looked at ways he could apply the insights gained to his own life and lifestyle, and to his understanding of other people and their choices. This allowed him to tap the inner strength hidden within. This detachment work is also a part of the process that Mala Betensky has developed in her phenomenological approach to art therapy. We have incorporated the activities of "contemplation" and of "detachment" into our approach described here.

Relational psychodynamics and phenomenological approaches in art therapy share much of Ignatius' methodology for making one's life come fully alive. These methodologies help one to face one's pain or issue; to acknowledge and own it; to move through it and accept the reality of its origins with their effect on the present moment. As a result one is able to choose to love oneself and others as God loves all; and to know that one is forgiven. This enables one to forgive the other person and oneself and to move beyond anger and hurt. To extend forgiveness is a decision of the will and a process into which one enters. This process may take a lifetime for some issues or relationships.

There are times that we can see things in our clients' artwork that they can not see or name. "I don't know what this is" is an acceptable response in art therapy, for the picture can reveal things from the person's unconscious long before there is any awareness at the conscious level. Sadly, it has been some people's experience that their honest answer of "I don't know" has not been accepted in verbal therapy situations. Like Julian of Norwich, a good Art Therapist sits still and waits until clients are ready to see the image, to work with it, and to explore it. There is a movement from the initial, outer sacred space of physical presence into a walk with them into that inner sacred place of the image and the relationship, always respecting their pace. Caring and present to them in their suffering, the Spirit working through the therapist gently draws out their inner strength.

What we present as a theme on any given retreat or workshop comes out of our own faith journey and struggles to be fully alive. While the people who seek us out for one-on-one spiritual direction, or for several days of retreat, or for sessions of art therapy are different than ourselves, there are certain blocks to healthiness that most of us face in life at some time or another. By being in touch with our own unique struggles we can have an openness to facilitate others in their unique struggles.

Christian writers have spoken of the "cloud of unknowing" and the "dark night of the soul." Although most people do not use the language of Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross, it is sometimes a crisis of faith in themselves or others which pushes them to seek help from a therapist or spiritual director. The anxiety and depression, which arise from their sense of loss and disruption of what has been comfortable or known, are very much like "boulders" on their shoulders, "dark clouds hanging over me." The boulders of sadness, fear, anxiety, anger, and rejection block not only psychological progress in therapy but also prayer and the healing process in spiritual direction. The "boulders" that cause the learning blocks for children are also the same ones that block the psychological and spiritual maturation of adults. The sources of these "boulders" or blocks are:

These "boulders" regress the adult back to a child's way of handling an incident or threat. Ordinarily articulate adults may spin around in verbal circles when faced with these feelings and experiences and feel stuck, especially when it takes more time than expected to "start feeling good again" or to "work through all of this stuff." Like children, there are times in the life of adults when they cannot express adequately in words what they are thinking in their mind, feeling in their heart and experiencing in their gut. A non-verbal, visual communication form may be needed to break through the barriers. Spontaneous art therapy may be the primary therapy or it may be a helpful adjunct to verbal therapy that will lead the person to enter a holistic healing process. It can be combined effectively with pastoral counselling/spiritual direction.Grief: unfinished grief due to a normal or abnormal loss; or interrupted grief; Abuse: physical, sexual, emotional or spiritual; Violence or an accident, whether to the person directly or by being a witness thereof; Abandonment: physically through illness, separation and divorce, or death; and emotionally through a verbal threat to abandon; and Repeated anxiety-provoking situations: those numerous small losses, uncertainties, and fears that come steadily in the child's life. These accumulate and rarely get processed and dealt with and are what disable the child and his ability to cope with even the usual ups and downs of everyday living. Unfortunately when left unprocessed, these get carried into adult life and become the "thorns in the side" and hooks for transference and projection and counter-transference when that adult is under great stress.

In stepping back from the artwork, they begin to look at the piece and life from a new perspective. This may lead to an understanding and integrating their life experiences. The "boulders" in their life become stepping-stones to a new path of seeing, observing, listening, being, acting and enjoying what they have created. Integration of the life experience enables and empowers the person to become healthier physically, mentally and spiritually. Although the product is an integral part of spontaneous art therapy, the emphasis is placed on the person and the process through which they go.

V.

Art Therapy Techniques and Directives

in

Pastoral Care --

Using

our Gifts, Talent and Knowledge

Art therapy is a very powerful tool. Untrained (in art therapy) mental health professionals who use art therapy techniques and directives are often surprised by how quickly art making can tap into and bring up material from the unconscious. While some of the art therapy literature states that doing art is safe,(22) that is not always true. For example, one problem that can occur in a workshop or retreat program when a facilitator wants to interpret another person's artwork or to analyse the art product from only an aesthetic point of view, rather than allowing the artist to tell the story behind his/her artwork.

Not to be done lightly or without awareness and caution

As an art therapy educator, I would like to state unequivocally that the incorporation of art therapy techniques into mental health and pastoral care work should not be taken lightly or without some deep thought not only to the directive being given, but also to the materials being set out and their properties. Included in Appendix D is a page on "Know your Materials." It is an overview of the materials and the rationale for their use by an Art Therapist.

Even some professionals are unaware that the material itself can send as strong a message to a client as the directive they may give. For example: there are many different kinds and colours of clay. The texture and colours are capable of evoking different responses. While self-hardening clay makes it easier for the participants to keep the piece without the bother of having it fired, it could also send the message that what the person does today is set in stone. If the group facilitator wants to send a message that this retreat time is an invitation to let God, the Potter, shape and reshape the participants or that this therapy session is an opportunity to work with changing an image of oneself, then it would be important to use pottery clay in an exercise meant for openness to ongoing formation. The dried up clay can be recycled. God, the potter, is reshaping us continuously. The use of self-hardening clay may be appropriate at the end of group therapy work to help the people concretize their experience of being in the program or to show the decisions or actions they want to take in the future.

Before giving any art material or exercise to a client, it must be used by the therapist several times and he/she should have done the written exercises also. This way, although the therapist is different from the unique individual coming for help, he/she, in some way, will be aware of what the material can bring up out of the unconscious. Obviously one should not use art therapy with anyone who over-stimulates easily or with someone who might be is psychotic.

The strength of a spontaneous art approach

There are many advantages to using a spontaneous art approach. These advantages reflect a relational psychotherapy approach to working with a client. Most important is the fact that in spontaneous art the client works at his/her own pace and to the depth that he/she is able. In addition spontaneous art approach:

Places the emphasis on the relationship and process rather than the product or aesthetics. Allows the person to choose ideas/issues that are most relevant to her/him or materials with which he/she is willing to work. The person is in control and responsible for their own work. Taps into the unconscious material and gives the person a visual voice when there are no words or few words to express what is deeply or painfully felt. May be a safer way to express intensity of negative feelings, thus offering a cathartic release and the possibility of working through these feelings. May enable a profound non-verbal communication with self and with the therapist/spiritual director as well as with group members. Works well in individual and group treatment process. May be abstract or realistic. The person chooses how much detail to put into his/her work. More can be added to the artwork at a later date. May be used with flexible themes/open-ended directives in a treatment or Retreat program. Is, over time, a concrete record of progress.

Creativity and Ignatian Method of Prayer

and Spontaneous Art Work

Life

Servants in a Contemplative Apostolate

Offering

a Compassionate and Gentle Presence

Included here are the outlines of the sequences used by Jacqueline Fehlner, RCAT, and Mala Betensky, ATR, in their respective work. They are followed by thoughts on how each fit into the work of Sr. Michael and Jacqueline Fehlner at St. Michael House and into Jacqueline's private art therapy practice. Some aspects of these seem to be present also in the Spiritual Psychology of James Olthuis.

The

Phenomenological Method of the Art Therapy Process

as

Applied in a

Spiritual

Direction/Creativity Session and/or in a Prayer Retreat

This is based on the art therapy work of Mala Betensky, ATR and on the spiritual direction and spiritual art therapy work of Jacqueline Fehlner, RCAT and Sister Michael Trott, CSC. Sequences 1-4 are done in silence and may be done alone or in the presence of the Spiritual Director. If this methodology is used as part of art psychotherapy, sequence 1-4 is done in the presence of the Art Therapist.

Sequence

1: Setting the Atmosphere

(This corresponds to Olthuis' "Letting in for a dance of trust.")

Sequence 2: Recognizing the StoryEntering the Quiet, a contemplative space Gather the art materials to be used in the quiet space. Choose the prayer/meditation passage on which you will focus. Decide how much time that you will allot to the creativity and prayer period.

Sequence 3: Getting Out the StoryCentering and Prayer Take time to become aware of your breath flowing in and out. Slowly read the prayer/meditation passage, aloud if possible. Reread the prayer or passage and put yourself into the story. Take a few moments in silence before proceeding to next step.

(This corresponds to Betensky's Sequences 1 and 2

and Olthuis' "Letting go" stage.)

Sequence 4: Owning the StoryThe process of artwork -- creative expression of the prayer/meditation or response to it. In silence, use your non-dominant hand to choose the specific materials/colours with which you want to work. (It may be helpful to do some pre-art play or warm-up exercises such as Scribbles, playing with the brushes to see what kinds of lines you can produce with them, tearing construction paper into different shapes and playing with them or arranging the random shapes into imaginary figures.) Begin your artwork and use the full time allotted.

(This corresponds to Betensky's Sequence 3

and Olthuis' "Letting out" stage.)

to

be aware of ordinary moments and ordinary people and to see the importance

that they hold. So much of our work as mental health professionals involves

helping our clients see that they are lovable and accepted as they are,

without judgment of their person or their art. We work at building self-esteem.

What one person sees as ordinary or is taken for granted may hold much

more truth or achievement than they realize. At this point I think of the

high-risk youngsters and the developmentally challenged people with whom

I have been privileged to work.

to

be aware of ordinary moments and ordinary people and to see the importance

that they hold. So much of our work as mental health professionals involves

helping our clients see that they are lovable and accepted as they are,

without judgment of their person or their art. We work at building self-esteem.

What one person sees as ordinary or is taken for granted may hold much

more truth or achievement than they realize. At this point I think of the

high-risk youngsters and the developmentally challenged people with whom

I have been privileged to work.