The Gospel and Global Climate

Change

by

Bob Goudzwaard

by

Bob Goudzwaard

Isn't it audacious to speak about "The Gospel and Global Climate Change"? Perhaps you suspect that I have forgotten what day it is: isn't Sunday the time for sermons? Rest assured that I do not intend to give a sermon. My plan is first to explore the issue of accelerated climate change, especially its cultural roots, and then try to make a link to the heart of the Gospel.

Let me, however, make a preliminary remark about the suggestion, occasionally made by politicians, that the Bible does not speak to issues like climate change. I doubt that very much. In the last book of the Bible, the book of Revelation, we find pictures of severe natural

plagues and disasters,

calamities strongly reminiscent of ones

happening in our own time — floods, the pollution of rivers

and

devastation wreaked upon the soil. The book of Revelation sometimes

accompanies these descriptions with the comment that the people were

not willing to repent (see Rev. 9:20-21). What does the word

"repentance" mean in this context? Commentaries on the Book of

Revelation usually interpret "repentance" only in a spiritual,

supernatural sense. But isn't it likely that these plagues or disasters

are actually rooted in human misbehavior? Texts such as these could

thus take on special poignancy today. They enjoin all peoples to repent

in very "natural" terms

— by changing

their patterns of use, of sharing,

perhaps even of production and consumption. That implies that we ought

not to read the Book of Revelation as a closed or fatalistic book. On

the contrary, it may hold open the possibility of conversion and

change, even change in human economic and political styles and

attitudes.

plagues and disasters,

calamities strongly reminiscent of ones

happening in our own time — floods, the pollution of rivers

and

devastation wreaked upon the soil. The book of Revelation sometimes

accompanies these descriptions with the comment that the people were

not willing to repent (see Rev. 9:20-21). What does the word

"repentance" mean in this context? Commentaries on the Book of

Revelation usually interpret "repentance" only in a spiritual,

supernatural sense. But isn't it likely that these plagues or disasters

are actually rooted in human misbehavior? Texts such as these could

thus take on special poignancy today. They enjoin all peoples to repent

in very "natural" terms

— by changing

their patterns of use, of sharing,

perhaps even of production and consumption. That implies that we ought

not to read the Book of Revelation as a closed or fatalistic book. On

the contrary, it may hold open the possibility of conversion and

change, even change in human economic and political styles and

attitudes. Climate Change

Let us now dig into the issue of climate change itself. I trust that we have all done some homework, that we have read at least some articles in the press about the causes of global warming. Perhaps most of us have seen Al Gore's impressive movie, "An Inconvenient Truth". That means that I can simply remind you that the gradual warming of the earth is closely linked to the growth of so-called greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, specifically carbon dioxide (CO2). In turn, greenhouse gas growth is inextricably tied to the worldwide use of fossil fuel energy (coal, oil and gas). The world's rising level of industrial production is dependent upon the use of fossil fuel energy.

Greenhouse gases have always been present in the atmosphere, but only after 1750, at the beginning of the industrial revolution in Europe, did their concentration in the atmosphere sharply increase. Sir John Houghton, the ex-chairman of the UN Panel on Global Climate Change, states in his Faraday lecture that since the beginning of the industrial revolution the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased over 35%. 1 It is now at its highest concentration in hundreds of thousands of years. Houghton estimates that if no action is taken to curb the emissions caused by oil, gas and coal usage, then carbon dioxide concentration will rise to two to three times its pre-industrial level during the 21st century. This implies a potential rise of average global temperature of between 2 and 6 degrees Celsius.

Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change

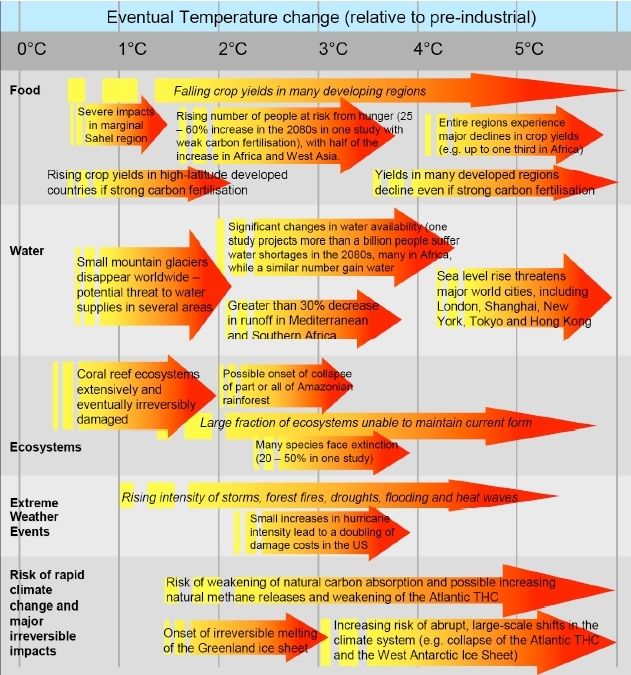

The so-called Stern Review, an outstanding report commissioned by the British Government and compiled by the most qualified scientists of that country, contains a chart which projects some of the consequences: 2 The lowest prediction is a temperature rise of two degrees Celsius over the entire century. The chart shows that even that rise will mean an increasing number of people at risk of hunger, especially in the northern deserts of Africa; the disappearance worldwide of all small mountain glaciers; a potential threat to water supplies in a number of areas; and extensive and eventually irreversible damage to coral reef systems.

Moving to a temperature rise of a three to four degrees Celsius, the chart suggests that hunger in Africa may increase from 25% to 60%, water supply in Africa and the Mediterranean will drop over 30%, and many species, from 20% to as much as 50% of current species, will face extinction. Hurricane intensity will double and the Amazon rain forest will partially collapse. Further, the melting of the Greenland ice sheet will become irreversible, which will bring with it the end of the permafrost. This in turn will bring huge amounts of hydrocarbon (methane, CH4) into the atmosphere, a greenhouse gas which is 25 times more effective than carbon dioxide.

Pacific islands and low coastal areas are already threatened by rising sea levels, but with a 5 degree temperature increase rising sea levels will threaten major world cities, such as London, Shanghai, Tokyo and New York. These are alarming — very alarming — predictions. They are not, however, the projections of people who live in a fantasy world, but rather the result of careful interdisciplinary research by teams of scientists with substantial expertise. Moreover, their findings are supported by a number of international reports, such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment Report "Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report," (November, 2007), and the United Nations Development Program's 2007 Annual Report, "Making Globalization Work for All". 3

All of this implies that the time has come to act decisively. Did not many people experience a sense of shock when watching Al Gore's "An Inconvenient Truth"? When even President Bush declares that climate change must be tackled in some way, then we can assume that we live in the presence of a real peril — after all, he is not a president who is prone to doomsday thinking. So international panels have been formed, and a number of proposals have been and are being formulated (from Kyoto, 1997, to Bali, 2007) to try to dampen the predicted consequences of global climate change.

Proposed Solutions

The main direction of these proposals is clear. The current solutions can be separated into three broad categories. The first is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by, for example, reforestation. Forests absorb carbon dioxide from the air to support their growth. The second category of solutions is to reduce the use of fossil fuel energy (coal, oil and gas) by implementing alternative, non-fossil fuel-based types of energy. Proposals include increasing the production of nuclear energy or promoting the use of less risky forms of energy production, such as wind and water power, biomass energy, hydrogen energy and geothermal energy (improved use of the heat inside of the earth). These proposals seek to improve "carbon efficiency". Carbon efficiency can be stimulated directly, such as through subsidies, and indirectly, such as through price controls or tax measures. As an example, the Stern Review heavily favors the introduction of a high "carbon tax".

Other proposals in this category call for new international, regional or global markets, some of which already exist. For example, the need to purchase "emission rights", such as the right of a country to discharge into the atmosphere a specified number of tons of carbon dioxide, may discourage the use of fossil fuel energies.

The third category — you will note that I am traveling at high speed through some of the current proposals — is to reduce the use of energy in relation to all that is produced and consumed, to decrease energy usage per product. This is the path of "energy efficiency". Energy can be saved in the spheres of both production and consumption. Here too direct measures are possible, such as through legal restrictions and prohibitions, as well as indirect measures, such as through the price system and a green tax system. For example, such measures would encourage the employment of more human energy (labour) rather than capital in the processes of production, transportation and distribution.

The Kaya Identity

So far, so good, I am inclined to say. Personally, I strongly favor most of these proposals, because they can make a significant difference.

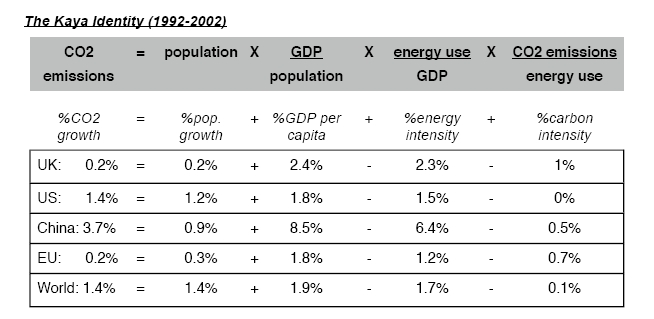

This difference can be illustrated with the so called Kaya identity. 4 The four columns to the right of the ‘=' sign can be read as a summary of the four components which together contribute to the total amount of carbon proposed solutions I described above, and it is dioxide (CO2) emissions.

Is It Enough?

There is something remarkable in all of the proposed solutions I described above, and it is this that I would like to draw to your attention to this afternoon, in the context of the Kaya identity. The question is whether improving the carbon and energy efficiency of all that is and will be produced and consumed is actually enough to do the job. I have serious doubts on that score. These doubts do not in any way diminish the need to implement most of the measures I have outlined. Three realities cause me grave doubt.

Financial Markets: The New "Big Brother"

The first reality is the enormous speed and volume of so many economic developments occurring in the global arena today, most of them in the context of the rapid process of globalization. We live in a time of a massive expansion of a number of global markets. Here I mention not only the huge growth of transnational companies around the world, but more particularly the fantastic growth and expansion of so-called financial markets. The amount of financial derivatives is now more than ten times the size of the combined Gross National Product of the entire world. 5 More international speculative capital flows around the world in a two-day period than the total amount of debt of all so-called less developed countries. We all know, I expect, how anxious most national governments have become over the dynamics of global capital, fearing what capital flows might do to their economies and societies. Often countries reduce their taxes on capital and capital movements simply out of fear of what this new "Big Brother" might do to them and their economies—as if financial markets have a life of their own. Obviously, this kind of financial dynamic does not dampen the worldwide growth of industrial production. On the contrary, it powerfully enhances production growth, with all of the consequences for rising CO2 emissions that follow. National economies are haunted by the financial markets. As a result, they continually increase their levels of production and exports in an endless search for the highest possible profitability. Is this not cause for deep concern, including in relation to greenhouse gas emissions?

A Multiplication Process

Let me state this point differently. In 1994 W. Corson, in a special edition of "Future" magazine, calculated that between 1950 and 1990 the world's population doubled, energy use rose by a factor of five and industrial production grew by a factor of seven. Figuring in world population growth over those same years, he estimated that the impact of human activity on the global South increased six-fold over that forty-year period. 6 Suppose now that this process of multiplication goes on for the next forty years, given so many dynamic national and international, political, economic and financial factors. Will the countervailing climate change measures I just summarized be adequate, will they be enough to have a substantial impact, even if they are implemented world wide? Or, in the terms of the Kaya identity, will not the dynamic growth of the first two factors of the equation (population growth and industrial production per capita) more than overtake the total gains achieved through improved carbon and energy efficiency?

Corson's calculations were made for the period between 1950 and 1990. We are now halfway through the next forty year period, but the tendencies remain exactly the same. What about a third period of forty years, after 2130? Bear in mind that the rapid development of India and China (and likely Brazil) must also be factored in.

The "Pro-Growth" Strategy

I have a second, deeper reason for serious concern about the limited scope of today's proposed solutions. I have referred to the important Stern Review, which is focused on the negative consequences of the global rise in temperature. The report clearly insists that there is an urgent need to cut back on the level of those emissions. But it strikes me that the entire report raises no questions about the increasing volume of industrial production, especially in the richer countries. On the contrary:

Tackling Climate Change is the pro-growth strategy for the longer term.

And it can be done in a way that does not cap

the aspirations for growth of rich or poor countries. 7

Why does the report make this statement? While other reports, such as recent Annual Reports by the World Bank and even the Al Gore movie, make hints in that direction, this statement is perhaps the most blunt. Of course, I understand that the poor countries urgently need further economic growth, simply to be able to cope with the poverty of the millions of their inhabitants. But what makes the undisturbed continuation of industrial growth in rich countries so important, so essential, that these aspirations are not even discussed? Did political considerations enter the scientific debate (then Prime Minister Tony Blair signed the report)? After all, there is no doubt that industrial growth per capita in the rich countries — the GDP per capita column in the Kaya identity — is one of the main sources of increased greenhouse emissions.

It would, however, be too easy or cheap to assume that the reason for this silence is political pressure. Perhaps, on the contrary, this statement is an honest one on the part of the authors. If so, then this then raises an important question. Do the authors of the Stern Review, along with many other experts today, put their faith, their ultimate trust primarily in new technological advances and new market or taxation devices — perhaps even to such an extent that they honestly believe that the rich countries can continue to increase their material economic growth almost forever?

A High-Speed Train

To illustrate that something like this faith may in fact be at work, consider a metaphor. The metaphor is meant to show that two entirely different views about powerfully dynamic developments within modern society can exist side-by-side. It is the metaphor of a high-speed train, like the French TGV, the train of grande vitesse, which travels at fantastic speeds across the countryside. The movement of a high-speed train can be viewed from one of two positions. The first perspective I call "the view from within". Imagine that you are traveling on a high-speed train, sitting in a comfortable chair. From that position everything looks quite stable and peaceful. You have no thought that the train may need to make an emergency stop; the journey continues without interruption. If you look outside the window, you see movement, but it is a virtual movement of the landscape itself. The landscape appears to be moving backwards, as if it is falling behind. This is an illusion, created by the fact that your own speed is your frame of reference. What is actually standing still looks like it is moving away behind you.

The second possible position is that you are standing outside the same high-speed train, a short distance from the tracks. This is "the view from the outside". What is your impression from this vantage point? It is that this train is traveling extremely fast, perhaps too fast. You may look ahead anxiously, fearing that the train may be threatening some children who are trying to cross the tracks farther ahead.

This metaphor illustrates that at least two different opinions of dynamic processes are possible. Each is specifically related to the point of view from which one perceives the movement. Standing outside the train, feet firmly planted on the ground, the view will be very different than the view from inside the train.

Suppose that as modern people we are inclined to identify ourselves with our own dynamic patterns, and so tend to view ourselves as an intrinsic part of that dynamic world. Perhaps this was the case for the authors of the Stern Review. You will agree that we will then be inclined to judge the outside world from that dynamic point of view. That implies at least two things. First, we will see and appreciate powerfully dynamic patterns in our societies as entirely normal. Our progress can and should go on. The famous Wuppertal Institute in Germany recently stated that future technologies will make possible as much as a 90% reduction of energy use per industrial product. In its view, this will solve the climate change problem. Experts always seem tempted to lean on even more far-reaching technological or market solutions.

Viewing the world only from the perspective of our own internal dynamics and capabilities usually has a second consequence. Increasingly, we will be inclined to see what is not moving as rapidly as us as lagging behind and therefore, to some extent, as abnormal. We may even begin to feel irritated by what or who is falling behind. How easily, for instance, we tend to perceive poor countries as underdeveloped, as straggling behind. Many people see poor men and women in modern societies as simply underperforming. In relation to the environment, the dominant view usually does not honor the earth's inherent limitations. Rather, nature or the environment should get out of the way. If the environment seems to pose limits on what we wish or desire, then we will be inclined to look at such limits as merely temporary barriers which our own technology or scientific achievements will overcome.

Clearly, burning behind all of this is a contemporary variety of the classic Enlightenment belief in human progress. Only this can explain the deep reluctance of so many people to entertain even the slightest consideration that sometimes we may need to take a step back rather than move forward. Perhaps we easily forget that as modern people we are brought up and educated in a rational universe of largely self-made, progress-related institutions, with the result that we naturally prefer the view from the inside, even to the profoundly dangerous point of identifying our own dynamic world with the real world. We then too easily make the operation of the market mechanism, for example, the ultimate orientation point within our dynamist universe.

The Re-Entry of Faith

This leads to the third reflection, which emerges from the view from the outside. It is not formulated by intelligent Western scientists but by the Asian churches of the South. They testify to what they see around them: the consequences of our deep attachment to our own self-made high-speed train in their life, environment and society. Let me quote some parts of a declaration written in Bangkok in 1999. It was written in the heat of the Asian Crisis by delegates of churches from the South as a letter to the churches and the societies of the North: 8

Letter to the Churches of the North

... Is there not in the Western view of human beings and society a delusion, which always looks to the future and wants to improve it, even when it implies an increase of suffering in your own societies and in the South? Have you not forgotten the richness which is related to sufficiency? If, according to Ephesians 1, God is preparing in human history to bring everyone and everything under the lordship of Jesus Christ, his shepherd-king—God’s own globalization!—shouldn’t caring for and sharing with each other be the main characteristic of our lifestyle, instead of giving in fully to the secular trend of a growing consumerism? ...How remarkably, even naturally, the faith perspective now enters into the picture! This is a perspective written from the heart. Many people in the South feel forced into a kind of economic adaptation and modernization which they would never choose for themselves. Often they ask themselves: won't this new type of dynamism demolish our culture and history?

We also sense in this letter a deep concern about our own modern, secularized Western attitudes. The word "sufficiency" surfaces in relation to our own consumption, and it is wonderful to see that in the view of the churches of the South, "sufficiency" is not related to pain and misery but to richness, to the joy of saturation.

In my view the pieces of the puzzle come together here. Climate change problems should lead us to reflect on the course of modern society as a whole from the perspective of restraint and shalom. There is both an external and an internal need to question the present course of production and consumption in relation to the profound vulnerability of human beings, of ecosystems and of the limited load-bearing capacity of the earth. If the train of production, consumption, and energy use forges ahead with us on board, with such extreme velocity and momentum, then what and who will survive?

For me, the upshot is that climate change solutions will fail if they do not therefore have a spiritual component, perhaps even an element of repentance at the outset. Let us be clear: it is not by accident that the second perspective, the view from the outside, starts from what is given to us and from what needs to be preserved, rather than from something we have made and produced with our own hands. The view from the outside is intrinsically creational. Only by putting first what is given to us by our Creator, and by granting priority to what needs to be preserved, can we begin to relativize the work of our own hands. Our own material progress is still seen by many people, including by millions of Christians, as the holy shrine of our entire existence and civilization.

What Then Shall We Do?

What then shall we do? I shall make two concluding remarks.First, there is a profound need to openly, even forcefully challenge the powerful illusion in our societies that our own technological progress and economic growth can save us. A spiritual battle must be fought against worldviews which do not start with respect for what the good Lord has given us to care for and preserve. The current political and economic order of thinking — first we need growth, and only then will we have the resources to provide care — is wrong. It must be attacked as thoroughly irresponsible. Christians especially, and Christian churches, have a task here. God willing, and they themselves willing, they can lay bare the deeply secular roots of the present illusions of our age. With the support of a growing number of more critical experts, they can help to build the capacity to break through the public lie that more material consumption in already rich countries will lead to more happiness. Precisely the opposite is true. This means that the message is primarily positive, not negative. The negative or shadow side of the message is that the more we continue down the present path of unlimited material expansion, the more we will plunder the earth, overburden vulnerable ecosystems, and engage in a rat-race for the final dregs of the world's depleted energy reserves, even if the price is war in remote areas. But the positive side is that a greater measure of peace, of shalom for all, can come through the timely acceptance of levels of economic saturation in material consumption and disposable income. Remarkably, more realistic horizons for our economies will emerge as a result. It may sound strange, but in the end working and consuming less will do more good for us, our children and the environment than endlessly trying to work harder, produce more and consume more. The principle of enough, of saturation, is an underdeveloped concept in economics and politics. But it can indeed open a door where other efforts fail.

My second remark is that there is hope for the future, in very practical terms. Hope cannot be derived from our own detailed blueprints for a relatively distant future. Real hope is not produced as a product but rather given through a kind of birth. It comes not primarily from us but much more to us. The sole condition is that our societies and communities consistently follow, step-bystep, a Way — a way which is guided by principles of care for the weak, and which, from the outset, contains elements of joy and relaxation. Stepping forward by stepping back (the Hebrew word for this is bechinnom, "giving up") is the unavoidable first step in the essential transformation of our own rich economies into truly sustainable economies.

A National Covenant

Let me become more specific. Imagine that, out of concern for the beautiful but vulnerable creation, and for the future of our own children, a public willingness emerges in modern rich societies like Canada, Great Britain, the Netherlands and perhaps the United States, to jointly refrain from further annual percentage increases in material consumption and personal income, especially when and where such increases lead to higher emissions of greenhouse gasses. This could form the basis for a national covenant, a covenant between employers and employees, chambers of commerce, the government, churches and civil groups and movements, to accept a general zero-ceiling in the growth of material consumption per capita. Such a covenant could then form the economic starting point for a gradual conversion of our national economies to more sustainable economies, somewhat similar to the way in which the British economy converted into a war economy between 1940 and 1945. Reduced material consumption growth frees up labour and resources to be used in other ways, namely to make a number of new investments or re-investments. Such investments could reduce the levels of environmental and ecological damage in each production sector, and would at the same time increase social capital, specifically in creating public space for care of the weak and vulnerable. Such a covenant would also make capital available to decrease the debt burden of the poor countries. Currently their debts compel them to pursue continually higher exports, which in turn require higher energy usage, resulting in increased greenhouse gas emissions. Finally, such a step creates additional economic room to stop deforestation and plant new forests, and to introduce everywhere, such as on the roofs of our houses, new forms of clean energy.

As this begins to work, and as it proves to be successful in terms of creating new forms of employment here and fewer burdens on the shoulders of the poor countries, important consequences will follow. Gradually we would bring down the material and energy activity levels of modern rich societies (the forgotten GDP growth column of the Kaya identity) — and so substantially decrease greenhouse gas emissions. A further hidden blessing will be that the current burdens of working too hard — stress, burn out — will significantly decrease, perhaps even disappear.

Shalom through joint self-restraint is economically feasible. In fact, restraint is highly desirable if it is done with an eye to the needs of others and the profound suffering of the earth. It is estimated that the number of special "holy days" in medieval times amounted to one-sixth of the total working days available. Far more time was taken off than in our over-productive modern societies. Is this not an almost entirely forgotten wisdom?

Blossoming Economies

Put differently, our economic horizon should not be the expansion but rather the blossoming of economic life, or more precisely (given the differences between cultures and nations) an orchard of blossoming economies, as the World Alliance of Reformed Churches has called it. 9 The metaphor of the tree surfaces here. In the internal economy of a tree all cells are fully involved in promoting healthy, blossoming growth; each is needed and none is excluded. That inclusive type of growth is possible only because no tree has ever has set out to expand infinitely in size, as we are still inclined to do in the rich countries. At a certain point in its growth, a tree displays a built-in wisdom to redirect its growth energies towards the production of fruit instead of height. If a growing tree remained focused solely on maximizing its height, it would cause damage to other living cells, perhaps even suffering and pain in God's entire creation.

Suffering and pain in God's entire creation— these words remind us of what St. Paul wrote centuries ago to the Christians in Rome. In Chapter 8 he describes the groaning of the entire created universe, clearly not just people but also animals, like coral reefs and polar bears. But the groaning of the universe is not without hope, because it happens as if in the pangs of childbirth. A new world is coming. "The created universe waits with eager expectation for God's children to be revealed" (Rom. 8:19). These are deep, remarkable words. They imply that the suffering earth looks to us today with expectation, waiting for us, in the hope that we will begin to live up to and uphold the standards which make us recognizable to the groaning creation as God's true sons, daughters and children.

ENDNOTES

1. Available at www.faraday-institute.org.

2. Sir Nicholas Stern, "Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change," Executive Summary, v. The full report and Executive Summary can be retrieved at

http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/independent_reviews/stern_review_economics_climate_change/ sternreview_index.cfm

3. Retrieved at http://www.ipcc.ch/ and

4. Taken from the Stern Review, Part 3, pp. 177-179.

5. Hedge Funds Research, Citigroup, and the Bank of International Settlements, BIS in Basel; quoted by the NRC Handelsblad, Economy section, February 24, 2007.

6. Cited in Charles Vlek, Lucia Reich and Gerhard Scherhorn, "Duurzamer consumeren, een economisch- psychologische analyse" (More Sustainable Consumption: An Economic-Psychological Analysis), in Van Grenzen Weten, Aanzetten tot een Nieuw Denken over Duurzaamheid (On Knowing Limits: Impulses To New Thinking About Sustainability), ed. by Koo van der Wal and Bob Goudzwaard (Budel: Damon/Pugwash, 2006), p. 123.

7. Sir Nicholas Stern, "The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change", Executive Summary, p. ii.

8. The letter is reprinted in its entirety in "Globalization and Christian Hope: Economy in the Service of Life", ed. Leo Andringa and Bob Goudzwaard, trans. by Mark Vander Vennen (Toronto: Public Justice Resource Centre, 2003) pp. 23-15. The consultation was organized by the South Asian Council of Churches, the World Council of Churches and the World Alliance of Reformed Churches.

9. See their report "Covenanting for Justice in the Economy and the Earth", offered to the General Council of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches, Accra, 2004. Retrieved at