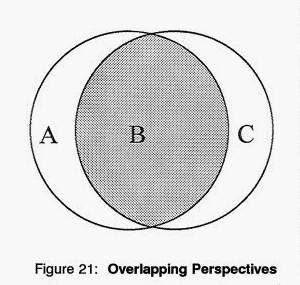

To begin, let us imagine the field of spiritual direction and the field

of psychotherapeutic

counselling as the overlapping circles in the Venn diagram above. The

B section represents a  common

and very large portion of the two fields; the A and C sections, their differences.

The differences between the two fields can be explored by making an analysis

from the A and the C stances, but to do this without an analysis from the

B stance downgrades both perspectives. For spiritual directors who lack

an appreciation of or fear psychology, a stress on the differences furthers

their inattention to the psychological realities of their directees. Likewise,

for psychotherapeutic counsellors who disbelieve spiritual realities or

who claim a more `scientific' or `value-free' approach, such a stress furthers

their inattention to and trivialization of spiritual realities in their

clients. Comparing the two fields from the A and C perspectives only, inevitably

leads towards stereotypical thinking and misses the ambiguities in the

B section of each perspective.(1)

common

and very large portion of the two fields; the A and C sections, their differences.

The differences between the two fields can be explored by making an analysis

from the A and the C stances, but to do this without an analysis from the

B stance downgrades both perspectives. For spiritual directors who lack

an appreciation of or fear psychology, a stress on the differences furthers

their inattention to the psychological realities of their directees. Likewise,

for psychotherapeutic counsellors who disbelieve spiritual realities or

who claim a more `scientific' or `value-free' approach, such a stress furthers

their inattention to and trivialization of spiritual realities in their

clients. Comparing the two fields from the A and C perspectives only, inevitably

leads towards stereotypical thinking and misses the ambiguities in the

B section of each perspective.(1)

However, when we reflect carefully on our own personal histories and on those of other people, it becomes obvious that a relationship with God often contributes to our emotional growth and integration. Many people who struggle with psychological difficulties find, in their relationship with God, strength to cope with life and to grow into greater human integration. Emotionally disadvantaged or challenged people often manifest a profound awareness of God's mystery which they find sustaining.

Common

Boundaries

In the mystery of the human person, it is problematic to try to separate

the fostering of emotional growth from the personal experience of God.

Spiritual experience is received in and for the totality of the human person

and his/her context of conscious and less-than-conscious emotions, desires,

feelings, deeper thoughts, etc., which have been affected by and have an

effect on one's personal history. While psychotherapeutic counsellors may

concern themselves primarily with one's emotional growth and spiritual

guides with one's relationship with God, most of the time these aspects

are intertwined and must be dealt with in an intertwined way. Consider,

for example, a directee who is having difficulties in coping with her peers

because she is not dealing appropriately with her own underlying hostility.

A competent spiritual director, at some point, would judge that her spirituality,

specifically as spirituality, is wanting unless she is also open to dealing

with the hostility that has been influencing her interaction with others.

Depending on his level of competence, the spiritual director would help

her deal with that hostility, some of which would be surfacing from her

less-than-conscious psyche.

Gospel

Sometimes Presumes A Mature Integration

Jesus said we could judge a tree by its fruits and that means on all levels

-- the God-and-me level, the you-and-me-and-us level, and the level of

our interaction with the broader world and its systems and structures.

He implied that spirituality, specifically as spirituality, is manifested

on, is affected by, and has an effect on, each of these levels.

When Jesus tells us not to judge rashly, he is pointing out how we are often more adept in attempting to remove a match-stick from our neighbour's eye than the log from our own. Psychology has come to name this phenomenon `projection.' But Jesus tells us that if we are to be authentic disciples, we should be dealing with our projections. He teaches us that calling our brothers and sisters "Raka" makes us "guilty of hell-fire." One who recognizes the potential destructiveness of one's own projections has a mature level of psychological awareness. The person, who can truly appreciate how calling one's neighbour "Raka" contains within it a movement that leads toward hell, is psychologically and spiritually quite mature.

Other teachings of gospel spirituality presume a similar combination of spiritual and psychological maturity. When Jesus says, "The Sabbath is made for human beings and not human beings for the Sabbath," he is implying a stage of maturity beyond that of the law-and-order stage of moral development.(2) Jesus is also implying a high degree of psychological integration when he tells us to "turn the other cheek." One has to feel good about oneself and have a sense of one's own self-worth to turn the other cheek. It is not the work of the psychotherapeutic counsellors alone to foster such a level of integration; it is also the work of mothers and fathers and teachers and social workers and spiritual directors and prayer guides.

The person who is called to die to oneself must have a "self" to die to. If a spiritual director is to encourage such a dying to oneself as he must, then he needs to help his directee have a strong enough self to which to die. A psychotherapeutic counsellor might need to encourage an overly responsible client to develop a strong enough self by taking less responsibility for others. A spiritual guide might consider such over-responsible behaviour a form of selfishness and sensuality and name the process of learning to be less responsible a form of `dying to oneself,' `mortification,' `carrying the cross,' or `self-denial.' While a co-dependent directee might find this very difficult to do, her spiritual guide, knowing how the process of moving toward mature responsibility develops through risking mistakes and/or doing actions which appear selfish, might encourage her to do it. In this process, she would be helped in moving from the `false self' to the `true self.'

On the other hand, a psychotherapeutic counsellor who does not lead a client away from self-preoccupation to placing other people's needs before one's own, at times and realistically, is practising a very truncated and harmful psychology. Psychotherapeutic counselling fails within its own realm when it does not encourage one's intimacy with self to be open to an intimacy with life which includes play, wonder, and some form of ultimate or deeper meaning. For human persons, such deeper meaning cannot happen unless one's personal growth is blended with a realistic concern for the common good and community beyond oneself.

Because they continue to reflect upon their respective skills from the A or the C stance, as illustrated in the Venn diagram above, some spiritual guides and psychotherapists continue to separate the psychological realm too much from the spiritual realm and vice versa. Unfortunately, psychology, along with its applied techniques in various forms of psychotherapeutic counselling, was born in the early part of this century when spirituality in the various churches was almost non-existent. Where spirituality did exist, as in the monasteries, its understanding and the articulation of this understanding were often reduced to the clear and distinct ideas of the prevailing rationalism. In addition, the churches, and consequently the spiritualities which they were supposed to foster, stressed institutional good over individual good. They also fostered the belief that the "really real" was from the neck up rather than from the top of the head down.(3)

Psychology leapt into the individual and affective gap and began to locate those aspects which spirituality always referred to as the "heart" or "inner person" or one's "depths" as being below a person's immediate consciousness -- the preconscious and the unconscious. It claimed for its own, the experience of human growth. As such, psychology was understood as personal and developmental while spirituality was stereotyped as static and something fixed.(4)

The use of psychological tools and therapies has become so universal with such perceived success in helping people to understand themselves and to cope with their emotional wounds that educated persons, in our present culture, are expected to be psychologically literate. This includes the skill of focused listening to one's own and another person's more significant feelings along with the knowledge of how human maturing processes are connected to both personal history and unconscious development. In all of the helping professions, the most fundamental level of listening to a person's experience is to listen for, hear, and notice how one expresses one's significant feelings and how all of this is related to the way one makes judgements about life. A helper has to know what the human experience means before he can know what it means in any other context including the faith context. Though persons in the various helping professions ought to stay away from using techniques in which they have no competence, not to use the skills and learning from knowledge based on the study of psychology and the art of psychotherapeutic counselling would be to render their own professions ineffective. As an educated adult, one cannot help but think in psychological categories. The real issue is to recognize one's personal limitations in their use.(5)

Like others in the helping professions in our culture, a spiritual director needs to be psychologically literate in order to listen to a directee's interior experiences. This basic literacy will also help him recognize his own limitations with regard to the use of more psychological techniques available to him. This basic literacy will help guard against the harm that can arise from projection and transference. Exceptions to the requirement of this psychological literacy occur with those rare persons who are so gifted by both nature and grace that they can compassionately read another's heart as Jesus did with the Samaritan woman at the well and with Nicodemus, who came to him by night. The stories around the giftedness of the Curé of Ars and Brother André of Montreal exemplify this. Persons such as these should not be bothered with this discussion. They already have a wisdom that training can not give them.

So far, I have attempted to make the point that spiritual direction and psychotherapeutic counselling are connected through psychological literacy. But there are also many other connections:

| 1) Both frequently

deal with common aspects of human growth such as grieving

issues and life-transition issues. 2) Both are concerned with the transformation of interior images since images of God are connected to images of self and to images of the world and vice versa. 3) Both use such techniques as the exploration of feelings, the reframing of the way one views and experiences negative situations, guided imagery to allow memories to emerge, remembrance and discussion of dreams, etc. 4) Both deal with the conscious and the less-than-conscious. 5) Both deal with the influence of one's history on one's inner life and outer behaviour. |

Differences

and Complementarities

On the other hand, it is not difficult to perceive their differences when

one compares the trained and focused skills of a psychotherapeutic counsellor

in unblocking past unconscious scars with the trained and focused skills

of a spiritual director attentive to movements happening in prayer and

in the directee's ongoing relationship with God:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In many situations, spiritual directors complement the work of psychotherapeutic counsellors and vice versa. In situations where spiritual directors and psychotherapeutic counsellors have the freedom and luxury to deal with the same client and have the client's permission to consult each other, their roles are very clearly experienced as complementary but different. In these situations, clients or directees observe that both approaches further some of the same interior processes. Such hands-on experiences manifest more clearly the distinction made above: whereas the psychotherapeutic counsellor's focus is on the self (the client's inner conflicts or character structures), the spiritual director's focus is on the person in relationship with other persons (the directee's relationship with God and through this with others in the world).

The

Healing Connection

Both therapists and spiritual directors use terms such as growth toward

wholeness, becoming integrated, becoming more human, wellness, etc. --

the implication being that both fields deal with the work of healing. Long

before psychology and psychotherapeutic counselling came into existence

as specialized knowledge with professional techniques for helping others,

psychic healing was always considered part of the work of spiritual guidance

and religious ritual.(8) The symbol of anointing

with oil and prayers for healing were part of prehistoric religious practices.(9)

Quite properly, spiritual guidance has always been involved with the healing

of the mind.(10)

Therefore, we must assume and take for granted that healing is one of the ordinary consequences of spiritual guidance according to our various traditions of Christian spirituality. Unfortunately, as it did over the centuries, popular religious culture, particularly now during the expectation of the third millennium, misuses this assumption by associating healing with cure, miracle, exercise of power, etc. Popular religious culture has obfuscated the nature of the healing that is more properly achieved through spiritual guidance; namely, the healing of meaning rather than the healing of integration.(11)

Healing

Of Meaning

In the Christian tradition, healing of meaning is ultimately not a matter

of good counselling and therapeutic techniques. It is finding the self

engaged in a relationship with God through one's encounter with the gospel

story of Jesus. Healing of meaning has more to do with learning to tell

one's own life stories and to re-establish them in the light of the gospel,

thus opening oneself for the acceptance of mystery into one's life through

the influence and companionship of God's Spirit. As suggested above, the

focus is not on the self and one's conflicts within the self. Rather, the

focus is primarily on one's relationship with persons -- the historical

and present community of persons present to us in our life now(12)

through the mystery of our caring God.

In this work of healing of meaning, spiritual directors may have to make

use of those same psychological techniques used by other professionals whose

main work deals with the healing of integration. At times, a spiritual

director's level of skill will not be appropriate for a directee's needs.

Then, like other professionals in our culture, he will need to refer his

directee to someone who has the appropriate level of psychological skills.

This need becomes quite evident when, after a period of time, a spiritual

director perceives that the spiritual-guidance focus is not sufficiently

helping his directee. Some simple illustrations can help us reflect on

the inter-relationship between spiritual guidance and psychotherapeutic

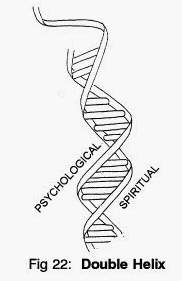

counselling. The first is the image the DNA model. The two strands of the

double helix in that model move in the same general direction. There are

cross-over bridges all along the way. Think of one strand as the path of

spiritual guidance and the other as the path of psychotherapeutic counselling.

At any point along the way, a directee or client may cross over to use

the other path to move along her personal life journey. However, sooner

or later, a person will inevitably need the healing of meaning of the spiritual

path which ultimately moves beyond the scope of the healing of the psychological

path.

whose

main work deals with the healing of integration. At times, a spiritual

director's level of skill will not be appropriate for a directee's needs.

Then, like other professionals in our culture, he will need to refer his

directee to someone who has the appropriate level of psychological skills.

This need becomes quite evident when, after a period of time, a spiritual

director perceives that the spiritual-guidance focus is not sufficiently

helping his directee. Some simple illustrations can help us reflect on

the inter-relationship between spiritual guidance and psychotherapeutic

counselling. The first is the image the DNA model. The two strands of the

double helix in that model move in the same general direction. There are

cross-over bridges all along the way. Think of one strand as the path of

spiritual guidance and the other as the path of psychotherapeutic counselling.

At any point along the way, a directee or client may cross over to use

the other path to move along her personal life journey. However, sooner

or later, a person will inevitably need the healing of meaning of the spiritual

path which ultimately moves beyond the scope of the healing of the psychological

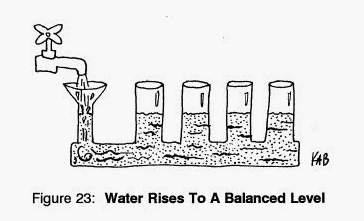

path. Another illustration

comes from elementary science. It is the image of the instrument used to

demonstrate how gravity causes water to seek the same level. If water is

poured into any one of the cylinders of the device, the water rises to

the same level in all the other cylinders. Each of the cylinders can represent

a perspective of understanding and dealing with the experiences of a person.

As "water" is poured into the spiritual-direction cylinder, in time, it

rises in the psychotherapeutic-counselling cylinder and vice versa, etc.

Another illustration

comes from elementary science. It is the image of the instrument used to

demonstrate how gravity causes water to seek the same level. If water is

poured into any one of the cylinders of the device, the water rises to

the same level in all the other cylinders. Each of the cylinders can represent

a perspective of understanding and dealing with the experiences of a person.

As "water" is poured into the spiritual-direction cylinder, in time, it

rises in the psychotherapeutic-counselling cylinder and vice versa, etc.

Healing

Of Meaning -- Our Spiritual Direction Horizon

The distinction between healing of integration and healing of meaning is

a "slippery" distinction. In practice, it can easily be lost. We are so

psychologically literate in our culture that we do not recognize this literacy

when we use it -- like the proverbial person who, one day, was surprised

to discover that he was speaking in prose. We now live and breathe psychological

literacy. Our movies and bookstores are filled with this reality. We

assume this way of thinking as the key way of understanding human experience.

Therefore, we can trivialize our own work of spiritual direction at those

times when we do not recognize that we are using only a psychological paradigm

in the work of spiritual direction and not a spiritual direction paradigm

with its specific instruments. In those moments, we run the risk of "doing

psychology in a faith context." Without such a recognition, we may foster

"cheap grace" through our unwitting use of cheap psychology.

Psychotherapeutic counselling often uses its tools and knowledge to help a client become freer in managing one's life by fostering the healing of one's psyche from the emotional effects of one's past history. Spiritual direction and spirituality, on the other hand, give a directee meaning and strength to use these and its own proper tools to live life meaningfully even when the effects of such obstacles are not totally relieved. This context of meaning is most aptly demonstrated through the theology and attitudes toward life implied in the following examples. They indicate moments in the spectrum of meaning for which a directee is disposed through the work of spiritual direction.

The first example is "The Serenity Prayer" by Reinhold Niebuhr. This is

a good summary of Christian spirituality. It is very consistent with many

other spiritual traditions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This second example is Pedro Arrupe's entry(13) in his diary towards the end of his life:

More

than ever, I find myself in the hands of God.

This

is what I have wanted all my life from my youth.

But

now there is a difference;

the

initiative is entirely with God.

It

is indeed a profound spiritual experience

to

know and feel myself so totally in God's hands

Both examples express the context of meaning of the spiritual journey of life. The first is from the perspective of the middle of the journey; the second is from the perspective of the end of the journey. You will notice that many of the themes expressed in these two pieces coincide with some of the themes nurtured through psychotherapeutic therapies: openness to the flow of life, self-acceptance, acceptance of life as it is, realism towards self and towards others, personal growth through transitions and crises. At the same time, there are basic differences.

In summary, spiritual direction is connected through psychological literacy to the study of psychology and its practices in psychotherapeutic counselling. Both spiritual direction and psychotherapeutic counselling involve healing. Psychotherapeutic counselling focuses primarily on the self and the conflicts which arise within the self that surface as a result of a crisis in one's world -- healing for integration. On the other hand, spiritual guidance focuses primarily on one's personal relationship with God and, through this, on one's relationships with others and the world -- healing of meaning.

The

Illusion Of Achieving Total Wholeness

If we observe and reflect carefully on the results of psychotherapeutic

counselling and healing in our own personal lives and in the lives of others

who are close to us, we can easily come to the conclusion that healing

of integration is never completely achieved in anyone. We can grow

in self-acceptance and become freer from those psychic blocks that prevent

us from engaging more fully in the flow of life. However, the primal scars

embedded in our psyches from our own personal histories and from the damaging

environments in which they took place usually remain with us. Most people

who are "in touch" with themselves and have done psychological work need

to keep acknowledging and disengaging themselves on different levels from

the effects of past wounds as they pass through the vicissitudes of life.

On this side of eternity, there is something of an illusion with our desire for complete wholeness or functionality or fulfilment or integration. This truth was always known in the past. Perhaps it was more readily accepted because life was so limiting and harsh. Most people were primarily concerned with survival; but over the past three decades, the knowledge explosion has led us to desire greater control over our lives. Many of us have come to believe that, in time, with the correct professional help, we can achieve full-scale freedom from our dysfunctionalities. Our discovery of human rights on a political level is transformed on a psychological level into my individual right to feel whole.

In our present popular beliefs about healing, we have come to expect that we can fix ourselves up by taking enough time to nurture our psyches. There is a belief that if we do enough inner work:

"I can escape from this terrible feeling of not belonging...." or ... "This dark hole in my heart ... I feel so empty! I need it to be filled before I can be happy...." or ... "Perhaps now I can finally be rid of this crazy fear...." or ... "If I get in touch with my feelings more, express them fully and attend to them enough, they will ultimately reveal to me all I need to know so that I will be completely healed...."Yet the reality is that, in most instances, these primordial scars and dark holes created in our psyches in early years never completely heal or get filled up. If I experienced abandonment as a child, I continue to experience abandonment as an adult, even after inner work and healing, particularly at those times when stress activates my vulnerabilities. Healing does not remove the historical circumstances behind those feelings. What usually happens in the process of healing is that one comes to a point of being able to accept and comprehend what has been, and then, to move on as one continues to learn how to avoid some of its more crippling effects in daily living.

Let me use a metaphor from our computerized culture. Within every word processing program, there are levels of hidden instructions that operate the program and determine both what appears on the monitor and what is ultimately produced. These levels default to the preprogrammed instructions. When a person using the word processing program does not specify the format, the hidden default system takes over. For example, if you desire your text to be justified on both the left and the right side, but your default system is automatically set up for the left side only, then you must reprogram it for this change. Sometimes, when a mistake is made or the computer has a glitch or circumstances make you forget to reprogram the hidden commands, the default system automatically takes over. In such situations, you have to reprogram the default.

Similarly, our personal histories determine the automatic default system in our psyches. Often, when we are in particularly vulnerable situations, our psyches tend to use their more inappropriate automatic default programming to cope. At these times, they need to be reprogrammed. Psychotherapeutic counselling has made great strides in giving us tools and options to reprogram our default systems.

Challenge

And Risk In The "Quasi-Safe Zone"

As one journeys through life and hits rockier paths, one may go through

a period where one requires trained psychological help to manage the rough

and threatening terrain of one's deep conflicts. Then, after a certain

amount of relief from these unresolved conflicts or after a deeper awareness

and acceptance of the sources of one's personal oppression, one begins

to experience signs of hope: "Some day soon, I'll be able to move ahead

on my own." This may be the beginning of the quasi-safe zone before the

goal of therapy is reached. When the client approaches this quasi-safe

zone, she needs to begin to take more responsibility for herself. As she

experiences more and more integration, she must both ask and answer for

herself these two important questions:

- How long should I place the forward movement of my life "on hold" before I consider myself healed?

- How much healing do I need before I am healed?

But the risk is a also a risk. One can abort the healing process that was begun, or one can be caught by a narcissistic self-concern in the name of safety or in the name of the expectations ingested from our culture. Nevertheless, often a living spirituality can give sufficient strength to the person in this quasi-safe zone to take responsibility for oneself. As noted above, it is the mark of healthy psychological growth when our personal growth is blended with a realistic concern for the community beyond ourselves. Spiritual direction, with its context of meaning, can dispose the directee for the strength and courage to exercise realistically this concern for the common good. Through the development of our own personal spirituality, we are led to a God who calls us to serve others even while we are still broken.

Spirituality, emerging from the competent practice of spiritual direction, leads us to be persons fully alive by embracing, rather than trying to escape from or to do away with, all our brokenness. Spiritual wisdom teaches that this can only be achieved through God's help in letting go of our need to fix up ourselves. On this rests the whole doctrine of grace as a free gift from God which is foundational to all the work of spiritual guidance.

Reflecting

On The Paradigm From Which We Really Operate

Now, after showing how connected and yet how different spiritual direction

is from psychotherapeutic counselling, I attempt to illustrate that, in

spite of their differences, many spiritual directors in our present culture

are, in practice, "mainly doing psychology in a faith context." I suggest

that, even though we use the language of faith and we believe that God

is active, the model we may actually be using in spiritual direction may

not be very different from the one being used by psychotherapeutic counsellors.

Therefore, at this point, let us consider our assumptions and values behind

our practice of ongoing spiritual direction. When we use the language of

faith and foster spiritual growth in our directees, what paradigms are

we actually using?(14)

Common

Approaches Of Most Spiritual Directors

Before we pay attention to our underlying assumptions, let me name the

kinds of things that most spiritual directors do during each session when

they help others spiritually. I'm quite sure most readers, including yourself,

would acknowledge the following without too much disagreement. In spiritual

direction sessions, spiritual directors usually:

|

Assumptions

Behind Our Common Practices

I think I am not far from the mark in articulating the following assumptions

which many of us have about our practice of spiritual direction:

a)

We usually deal with the "intra-personal" and interpersonal levels before

we move to the societal levels.(15) We

do this in each session, and we do this over a series of sessions in the

long term. Accordingly, we expect a sense of wholeness in directees before

we consider them able to embrace a call in the societal realm. This approach

with its corresponding expectations can be verified by reflecting on the

experiences of faith/support/prayer groups in our culture. In those groups,

the transition from interpersonal to societal presents an enormous hurdle.

b) Since the 1960s, we have become more and more aware of the influences of past emotional wounds. We have come to use many of the techniques available in our culture to deal with issues we all meet in spiritual direction. For example:

empathic listening skills, journaling, incest and sexual abuse studies, Enneagram and Myers-Briggs typological matrices, art therapy techniques, dream interpretation techniques, twelve-step technologies.

Through these techniques, along with counselling skills in a faith context and the use of meditation, many of us help directees deal with issues in such areas as:

mid-life transitions, incest and sexual abuse, inner child, grief recovery, relationships, aging, toxic shame, female and male empowerment, addiction, acceptance of one's humanity.

c) We take for granted that persons must feel good about themselves before they can respond to God in a healthy way. The phenomenon of interior healing within a faith context occupies more and more of our time with people who come for spiritual direction.

d) We take for granted that emotional readiness must precede encouragement for growth. Like other professionals, many of us are more or less skilled at waiting for a person to be ready before we propose a growth-producing question or a needed challenge. This means that we do a lot of listening and a lot of waiting, but very little teaching. We believe that spiritual health is linked intimately with emotional health. We take for granted that there is a true self which somehow is imbedded in a person's subjectivity. Thus, we believe that we must encourage the individual to come to one's own awareness and live according to one's personal true self.

In order to verify whether the assertions made in a) through d) above are some of your own assumptions, it may be helpful at this point to consider the following set of questions. From my viewpoint, these questions incorporate most of those themes which spiritual directors should deal with when engaging in their skill or art. In the light of the Venn diagram at the beginning of this chapter, these questions touch upon the kinds of themes spiritual directors would use if they were to operate from both B (common area) and A (differentiating area) sections. To verify these assumptions, reflect upon your own experiences of receiving spiritual direction; or focus on your own modus operandi in guiding others; or, if you prefer, reflect upon the ways that spiritual directors talk among themselves about practical issues of spiritual direction.

Some material for your study, reflection, discussion .....

The following 20 questions/comments are placed here to help you consider this question: What areas do spiritual directors usually explore in spiritual direction sessions? Obviously no two practitioners will explore issues through questions and comments in the same manner. The sentences below are merely suggestions. They represent the themes that spiritual directors might explore. Beside each focal area, estimate its frequency of use in spiritual direction sessions: (1) hardly ever; (2) occasionally; (3) often.

1. How did you feel about that?6. What Grace do you need now?

2. It seems to me that you have to learn to forgive yourself?

3. You seem to experience a lot of anger (shame/fear/embarrassment) around

that.... Try to express that to God.

4. You are learning not to take responsibility for everything ... learning not to live

up to your expected role! Another comment in this category might be: The way

you need to control things seems to be an issue here.

5. Go back in memory, relive the experience, and ask Jesus to come into

the scene.... Let your feelings surface and allow Jesus to deal with this memory.

7. Would you name that experience as Consolation or Desolation?

8. I hear that you are indeed experiencing Consolation, but is it like a drop of water

on a sponge or on a stone?

9. How does the quality of the Consolation you experienced this past week differ from

the Consolation which you received when you were praying over that such-and-such

issue the week before (or at some other point that is recognized as being significant)?

10. What is the social history that has given rise to that situation? How does our14. What mystery of Jesus' life are you being called to manifest in this situation?

present culture influence that situation?

11. In that situation, what is the influence of money? Who benefits? Who loses?

12. In that group (community/family), who exercises the real power?

13. What symbols (values/language/ideology) are used to legitimate this

situation? What existing invisible patterns or structures never get questioned in

the situation? What are the unwritten rules that allow this situation to take

place?

15. How does the manner in which you are putting so much effort into that project

harmonize with our belief that God's gift of grace is a free gift? How might our belief

that we are created and limited by time and space relate to your anger around the

such-and-such limitation you experience?

16. What is your operative theology and how does it harmonize with your stated theology

or belief about that?

17. What Christian belief does your experience illustrate (or call for)? Why?

18. If you were to consider the executive body of your church as representedThe purpose of this reflection is to show that the focal areas to which spiritual directors often attend are emotional and/or healing issues on the interpersonal level; far less frequently do they focus on areas that deal with social systems and societal awarenesses, or with theological-principle awarenesses, or with the technical language of the Exercises and discernment.

by the Samaritan woman at the well, how would Jesus respond to her?

What would "living water" be for that executive group? What would Jesus

say in the place of "go tell your husband"?

19. You experienced a great deal of healing during the past week by praying the

Lazarus story, particularly when you heard Jesus call you forth from

the tomb.... Now pray this again, and in your imagination, let the whole

situation in which you find yourself be Lazarus.... Wait in prayer until you

hear the voice of Jesus calling to that whole setting, "Lazarus, come forth!"

20. You described that business meeting very well and have shared your personal

evaluation. Was the group in Consolation or Desolation when such-and-such

was taking place? How did that meeting manifest the experience of the

Beatitudes?

- Focal areas 1 through 5 represent the psychodynamic perspectives and issues associated with the psychological level.

- Focal areas 6 through 9 are associated more with the explicit use of the technical language of the Spiritual Exercises and discernment.

- Focal areas 10 through 13 are associated with the social structures and the systemic environments that impinge on a directee's personal experience.

- Focal areas 14 through 17 are samples of theological reflection which make connections between theological truths and a directee's life experiences.

- Focal areas 18 through 20 focus on communal-societal perspectives that affect, and are affected by, a directee.

Where do our assumed approaches come from? In general, our assumptions emerge from a different way of experiencing and understanding our world. In western culture we have shifted from the classicist worldview(16) to a more developmental worldview. It is a shift from the realm of theory to the realm of experience -- from external ideals and conformity according to a fixed mode of understanding ourselves and our relationships with each other to a more developmental mode. This shift occurred throughout the western world during the two decades following the Second World War. In the Roman Church, this shift was stimulated by the Second Vatican Council. It has affected our images of self, work, Church, God, Jesus, etc. Our new horizon(17) has made a difference in the way we view ourselves, our directees, and the universe in which we live. Here is a partial listing of various aspects(18) that have resulted from this shift:

|

|

|

| Truth is believed to be objectively known and absolute. It can be arrived at rationally. Objective truth is the measure of subjective experience. More importance is given to deductive learning and the application of principles to given situations. Stress is on the interior logical coherence of an explanation. | Truth is believed to be relative and dependent upon new data. Therefore, it is measured by experience. More importance is given to inductive learning from the data of experience. Stress is on statistics. |

| Life is understood in terms of fixed and permanent categories. | Life is understood developmentally and historically; life's meanings are affected by time and place. |

| God's revelation is given in a fixed way and can be believed and taught independently of cultural meanings. | God's revelation is through symbol and is conveyed with images and metaphors. |

| Decisions are made in secrecy and through hierarchical structures. | Decisions are made by participatory structures and more consensual approaches. |

| God's will concerns the exact means. | God's will primarily concerns our final goal, our salvation. We are responsible to discover the means. |

| We are to discover God's will which is already out there known. | We make God's will; we are responsible. There is need for discernment. |

| We make use of the things of creation for the purpose of attaining salvation. | We are co-creators with God within creation of which we are a part. |

| Moral decisions are made by applying principles in a deductive way. Morality can be determined in separation from spirituality. | Moral decisions are made by a coalescence of values with an honest regard for the principles involved when various principles conflict. Morality and spirituality are not separated. |

| Spirituality is understood primarily as a person's private affair with God. Interactions with the world are regulated by obedience within a context of charity and prudence. | Spirituality is understood as interpersonal and social. Charity comes before obedience. Conscience is key. |

For a long time before this shift took place, most articulated spiritualities distrusted feelings and the role of individual conscience. They emphasized an external, objective, and rationalistic understanding of the world. As a result of this shift, we needed to revisit the human experiences behind our spiritual and theological insights. We needed to understand each other and our world from a developmental perspective. With the stress on Cartesian clarity, with a theology rooted in rationalism, and with a loss of a sense of biblical symbol, we had no way of doing this except by using those instruments and methods that were easily available to us through our culture. Consequently, we spiritual directors absorbed the methodologies that were more accessible for us to attend to the interior subjective experiences of our directees and to develop a language to speak about them.

Language

of Pietism, Existentialism, and Psychology

The study and practice of psychology, so much a part of the culture at

the time of this shift, gave us important ways of attending to interior

experiences. Pietism complemented this by affording us a simple way to

speak the language of the heart with phrases and words coming from our

Christian heritage.(19)

The exaggerated use of psychology, which can be referred to as psychologism, makes the self an object to be fixed up -- that is, if I know myself enough, if I allow myself to enter into my own unconscious, I will ultimately be able to bring myself to wholeness. Psychologism pays attention to the past in terms of the psychic, structural and emotional development in one's personal history. Often it pays little or no attention to the structures of society in which that personal history has taken place and to the continued forces of injustice which these structures perpetuate in our psyches.(20) Furthermore, it pays no attention to the basic insight of Christianity that we are radically incapable of achieving our ultimate goals by our own efforts; we cannot save ourselves without the free gift of grace.

Pietism goes back to the reactionary times of the great theological debates after the Protestant Reformation when theology became abstruse and separated itself from the ordinary people. It has affected us in many different ways such as in Methodist- and Charismatic-type movements. It is a way of thinking and speaking about God's mystery from a more devotional and tender point of view. It can be uncritical in judgments about one's own life context, emphasizing one's personal, private, devotional experience in separation from one's societal experience.

The other factor that has influenced our methodologies in spiritual guidance is a kind of existentialism that has become an accepted part of our Western culture. During the past hundred years, this philosophy has emphasized the self as the centre of one's own activity and the self as the centre of its own meaning.

You can notice these influences in the multiplicity of ways we help directees attend to their deepest selves. We help them notice their interior experiences and bring these into their affective relationship with God. As we do this, we help them notice how these deeper feelings have been affected by their own personal histories. We spend many hours encouraging directees to be in touch with themselves, to find God within, and to discover ways they can grow in personal healing. Often directees come to us for spiritual direction precisely for such discovery and growth. I suspect that most of us spiritual directors seldom spend time with our directees analyzing how culturally induced is their expectation that personal wholeness is possible.

Danger

Of Fostering Reverse Perfectionism

Without such an analysis, we run the risk of perfectionism. Within the

classicist worldview, spiritual directors had to deal with external perfectionism

since growth in perfection was understood in terms of an objectively knowable

world. Directees within that frame of reference often dealt with exactness

in exercising religious practices, distractions in prayer, practices of

obedience, proof of one's goodness through external manifestations in good

works. Scrupulosity concerning the fulfilment of external rules was very

common. On the other hand, in a developmental worldview with its stress

on knowing the truth experientially and through one's own interiority,

we can communicate a reverse form of perfectionism:

- Knowing oneself thoroughly;

- Dealing with all of one's issues;

- Needing to be certain about the options that will bring about maximum personal fulfilment.

Individualism pays attention to "my personal good" before the common enterprise. Individualism holds as self-evident the desirability of fulfilment and the possibility of wholeness. Individualism believes that the common good of marriage, of community, of cooperative work, etc., rests on the attainment of these desires within each individual person. The striving for the achievement of these desires to be authentically whole easily leads spiritual directors into the trap of encouraging too much attention to a directee's uniqueness in the name of integration and wholeness, thus contributing to inappropriate individualism.(21)

Consequently, we should ask ourselves: "What paradigm do I use in my practice of prayer guidance?" I suggest that many of us directors mainly use a psychotherapeutic model. Because of our own very psychologically literate culture, we cannot help but stress the healing of integration of a psychological model. In our attempt to lead directees to greater freedom in becoming disciples of Jesus, we easily slip into those approaches culturally accessible to us.(22)

Some material for your study, reflection, discussion .....

1. Do you agree that we operate primarily with a psychotherapeutic paradigm in spiritual direction? If not, how would you name the paradigms we do use?2. Which of the following adult concerns in our society are/are not reflected and encouraged with the paradigm(s) we use:

3. With what classes of persons do we spend most of our time in the ministry of spiritual direction -- business persons? unemployed? blind people? prisoners? upper middle class? lower middle class?

- Political involvement;

- Relationship between the various experiences of life and our belief system or theology;

- Relationship between the editorial page of the daily newspaper and the Awareness Examen;

- Relationship between some public event and the Grace being sought;

- Actual involvement with the marginated.

Developing

A Spiritual Direction Model

In

The Light Of Its Proper Horizon

When a spiritual director helps his directee articulate and reflect upon her interior experiences from the perspective of her relationship with God, he implicitly uses insights and approaches from many fields of knowledge to help discern what is being expressed. The domain of spirituality, with its applications in various forms of spiritual guidance, is and needs to be interdisciplinary. Historically this was always so, especially in the days prior to the development of the scientific method and the specializations that subsequently followed.

By the twentieth century, spiritual direction was associated with that branch of theology known as "ascetical theology" which, in turn, was relegated (in the prevalent classicist worldview after the age of rationalism) to the understanding and categorizing of the different virtues, signs of holiness, and states of ordinary and mystical prayer. Consequently, by that time, spiritual guidance had little to do with human growth and development but a great deal to do with the monitoring and guiding of external behaviour. Attention to human growth issues has only been put back as an essential component of spiritual direction since the shift towards a more developmental worldview and the consequent need to rediscover, through experience, our personal relationship with God.

As we discussed earlier in this chapter, psychological literacy was very important in reclaiming the role of attending to experience when dealing with spirituality. I suggested, however, that, now, many directors use only a psychotherapeutic paradigm and do so unwittingly. I implied that, if this is so, it is not adequate. Human experience is much broader than the focus of the psychotherapeutic paradigm. Spirituality involves the totality of human experience since it embraces values, worldview, ultimate meaning, and personal relationships with other individuals, with the world, with the cosmos. One's spirituality affects and is affected by all these aspects. Therefore, we have to go beyond the psychotherapeutic aspects of our art and emphasize more explicitly the theological and `communal-societal' aspects. In other words, our model must make more explicit use of the context from which we operate.

Making

Explicit What Is Implicit

There are two essential aspects of our context that are part of our covenant

and implied contract in every session with our directees:

- 1. We expect that we will use gospel spirituality as a key value. In the Ignatian tradition, this is often mediated through the language and structures of the Exercises which present quite explicit ways of focusing the gospel.

- 2. Both director and directee should expect to operate from an adult paradigm of spirituality which, at this time in our history, should manifest the value of transcending oneself by working in the larger world to develop a realm of inclusivity and justice for all.

If we were not living in postmodern times, the psychotherapeutic model alone might be appropriate since our directees would have an explicit identity shared with the director and a community of others. In our postmodern situations with countless levels of pluralism even in the very supportive communities in which directees may participate, this lived identity can no longer be taken for granted.

An event, very symbolic of our situation, continues to intrigue me. It happened in the early 1980s when I was invited to facilitate the process by which three directors of a religious novitiate evaluated their formation program. At some point in the evaluation process, we began "to walk around" the issue of identity. We discussed the point that although the novices showed a great sophistication in their interpersonal relationships, they seemed to lack the basics of their Roman Catholic heritage. Then I made a comment: "Since the novices do not have a common training in the basic catechism and the accepted practices of their faith, wouldn't it be helpful if, as directors of the formation program, you were to teach and give certain guidelines concerning this basic area? For example, wouldn't it be wise, as an ascetical practice, that each novice make use of confession (Sacrament of Reconciliation) every three months or at least once during each liturgical season?" Well, they shot me down. They would not consider the value of establishing such a guideline! I believe they were actually using a psychotherapeutic paradigm for their judgements.

In our work of spiritual guidance, we default to the common denominator of the psychological literacy of our culture if we do not articulate explicitly our understanding of theology and the vision of our world that it implies. To move away from over-emphasizing the psychotherapeutic model, our context needs to be made explicit, not only in ourselves but even with our directees.(23)

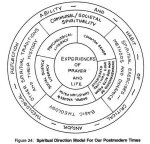

Figure 24 illustrates the aspects of a model of spiritual direction that a trained, Ignatian, spiritual director in our culture should be using:

click here

b) The next circle represents the aspects of a spiritual director's immediate listening perspectives, many of which would be expected of an educated Christian adult in our present culture:

- Adult literacies such as the psychological, sociological, environmental;

- Appreciation and some understanding of how God has been working in his own life;

- Basic understanding of his own faith heritage with some appreciation and familiarity with the directee's faith heritage;

- Basic understanding of the themes, symbols and values of the whole bible and, particularly, of the New Testament.

- Methodology, dynamic, and theology of the Exercises (*);

- History of spirituality;

- Social analysis (*).

d) The fourth circle represents the level of `theological reflection' (*) which can generally only take place after data from the other circles has been gathered and somewhat understood.

I believe that all these perspectives should comprise the mental framework of a fully trained, Ignatian, spiritual director in our Western culture. However, at this point in time, as discussed above, such implicit use of these aspects at the back of a spiritual director's mind is not sufficient. I would suggest that, as a spiritual director listens to and helps his directee to explore her experiences of life and prayer, the perspectives indicated by an asterisk (*) need to be used in a more explicit way. Before I discuss and illustrate how these perspectives can be used to make our implicit context of spiritual direction more explicit, let me discuss what may appear to be a digression -- the importance of Theological Thinking in spiritual direction.

About

Theological Thinking In Spiritual Direction

Whenever I personally experience or witness this skill being used well,

I realize that its users deal quite adequately with many of the different

aspects of the model. They use Theological Thinking primarily as a way

of making their judgements internally. A perceptive directee would hardly

notice this skill because it is internal to the guide. On the other hand,

some spiritual directors use this skill quite noticeably in their conversations

with their directees.(24) When this skill

is possessed by a spiritual director in more than an intuitive way, it

seems to foster the more explicit use of our spiritual direction model.

Theological Thinking is a way of thinking used by those spiritual directors who have appropriated their theological training and education so well that they consciously employ the concepts and language of theological discourse in their ministry of spiritual direction.(25) Often they perceive and understand issues of human experience from a theological viewpoint in preference to other viewpoints. In spiritual direction, they have developed the discipline of perceiving the implied theological principles behind the experiences of their directees and of using these principles in the discerning activity.

Internal

Use Of Theological Thinking

Instead of thinking about a directee's need to accept herself either in

a generalized fashion or in a more psychological mode, they perceive the

issue more from a theological viewpoint such as:

- Her need to experience God as accepting and loving her as she is and, consequently, her receiving the courage to accept acceptance;

- Her need to experience what it means to be a created being -- her creaturehood;

- The need for God to reveal sin or for her to experience forgiveness;

- Her lack of belief in the Incarnation or in the real humanity of Jesus.

External

Use Of Theological Thinking

Other spiritual directors use this skill quite evidently in their spiritual

direction conversations with their directees. If we were privileged to

be present at some of the spiritual direction sessions in which a spiritual

director used his Theological Thinking in an explicit manner with some

of the above directees, we might observe something like the following:

(In returning

to some of the previous examples, I assume that there is only one spiritual

director (Sean) who is accompanying the different directees. Let me also

employ the following code:

-- TT shows

a use Theological Thinking as an internal, mental framework only;

-- PL shows

the use of Psychological

Literacy;

-- ME shows

the use of the Methodology of the Exercises;

-- ETT shows

the use of Theological Thinking as an external instrument in the conversation

that takes place in the spiritual direction session.)

-- Sean accompanies Jean -- The setting is a weekly spiritual direction session during the notation-[19] Exercises journey. Sean has been exploring with Jean what the trigger was for her Desolation (ME) and has been listening to and "tracking" the feelings of anxiety and guilt that she was experiencing (PL). From many clues during the last session and this present one, Sean perceives that Jean probably has an underlying false belief that sin makes her worthless (TT). At some point Sean says, "Jean, you have recognized that this experience you are having is a form of Desolation (ME) and you have told me how guilty you feel when you react in such a way (PL). What is so bad about admitting that you are a sinner? What would this admission do to you?" As they discuss this at some length, Sean perceives that this intervention has been valuable (ETT).... At a later time toward the end of the session, he encourages Jean to make some Repetitions in the next prayer exercises by returning to the place in the same scripture text where the Desolation began to occur (ME). He reminds her to bring the fruits of their theological conversation (ETT) into the Repetitions and Colloquies (ME).

-- Sean accompanies Melinda -- During a weekend program geared to teaching participants how to pray with scripture, Sean discovers that, in prayer, Melinda feels only what she should feel and that she cannot allow herself to be more passive in prayer in order to let her real feelings surface. Her relationship with God is almost contractual (TT). No doubt there may be many causes for this, such as the fear that she had as a younger girl of expressing her real feelings before her older abusive brothers (PL). For several reasons, time being one of them, Sean decides on an intervention that is more of a Theological-Thinking intervention. In the course of their dialogue within the session, Sean says: "It seems to me that you have been expressing yourself in prayer according to some contract. You seem to say the right things and to feel the right feelings in order that God will be pleased with you...."

Notation [22] of the Exercises suggests another way by which a spiritual director, with this developed skill, can use Theological Thinking. It is to engage a directee quite obviously in a reflective dialogue concerning her operative theology concerning such-and-such. Below is an example:

-- Sean accompanies Beverly -- During the last third of the Second Week in the notation-[19] Exercises journey, Beverly went into Counterfeit Consolation and then into a kind of confusion during which she spent several days being upset. Nothing could account for her being upset except what was happening in her prayer (ME).

She has always been the kind of person who needs to make sure that what she is doing is significant (PL). Over the years, this has been transformed into a desire to do something significant for God. She has grown in spiritual maturity and is authentically generous. Earlier in the Exercises journey, Sean recognized Beverly's need for the Second Set of Guidelines for Discerning (ME).

In the decision-making process this past week, she mistakenly chose one alternative because she took for granted that it would be more in keeping with God designs. It was also the harder thing. She took for granted that the harder thing was more significant (TT). In the course of their dialogue, Sean says: "Beverly, I heard you say that you chose the harder of those two alternatives because you wanted to choose what would be more significant. What makes you think that the harder alternative is the more pleasing or more significant one in God's eyes?"

So a dialogue proceeds about whether it makes good theological sense that the harder thing is the better thing and about what carrying the cross means. Their dialogue even moves towards talking about our role in redemption (ETT). In the course of the session, Sean helps Beverly uncover the Temptation Under the Guise of Light [332] and helps her make note of this for the future [333] (ME).

Except for the faith perspective, this is a bit like cognitive therapy during which a therapist might engage a client in examining his/her thinking to ascertain whether certain lines of thinking lead to destructive self-talk which, in turn, lead to unwholesome emotions.

Evaluative

Comments About Theological Thinking

There are times when a spiritual director might use this Theological Thinking

in even more obvious ways than I have suggested in the above examples.

When he does it effectively, how does it further a directee's interior

spiritual experience when, on the surface of things, it seems to be heavily

cognitive and superficially affective? I think it works in this way. The

spiritual director engages his directee in a discussion on some theological

point relevant to the directee's experience. Through this discussion, the

directee's experience is further engaged, and then, later, through

the directee's own prayer, the very process of the directee's spiritual

experience is advanced. These further observations may be in order:

- Such a guide uses his cognitive training in biblical and systematic theology in his ministry of spiritual direction much more than I have been implying throughout this manual (e.g., as in Chapter Seven).

- Whether a spiritual guide's use of Theological Thinking is internal or external, this skill, exercised appropriately in combination with a practical intuition before the mystery of a directee, often includes many of the other perspectives of the spiritual direction model I am proposing.(26)

- Though all spiritual directors need a certain amount of theology, it seems to me that the skill of Theological Thinking, as I have described it above, is not a prerequisite for competency.(27)

From observation, it seems to me, there are competent spiritual guides who do not possess the skill of Theological Thinking in such a definite mode. They make use of their life of faith with its inherent theological principles. Their theology is often more intuitive, arising from a generalized sense of the faith or from a deep-felt knowledge of the scriptures. However, it would seem to me, these spiritual guides do have the ability to reflect critically upon their directees' experiences and even if this skill is not obvious to their directees or to their colleagues who may be more theologically articulate, it is present internally in their practice of discernment.

Reflection itself is a natural human process by which one thinks about and judges some object or event. Critical reflection is the same natural human process but with a more disciplined focus which involves an analysis of the different aspects of its subject and an evaluation of their significance in the light of other relevant frameworks of understanding. Critical reflection, like the natural process of reflection itself, admits of many different levels of sophistication. In fact, the purpose of education in most fields is to develop the skills of attending, describing, delineating, differentiating, evaluating, understanding and judging, all of which are aspects of critical reflection. My point is that theology is not the only relevant framework in which a spiritual director has learned to reflect critically.

Some

material for your study, reflection, discussion .....

What kinds of education, other than theological, would help a potential

spiritual guide develop the skills of attending, describing, delineating,

differentiating, evaluating, understanding and judging, that may be required

to:

- Recognize that the directee's experiences are always different from his own even though the directee may be using the same words that he used about his own experience?

- Determine that a directee's good feelings are not the same as Consolation or that her bad feelings are not the same as Desolation?

- Help a directee isolate a key issue from among a confusing set of lesser issues?

- Help a directee differentiate the Afterglow from the moment she received the Consolation Without Cause?

- Respond to a directee who makes this statement: "I find myself walking and talking with Jesus in my Gospel Contemplations. I appreciate what is happening but I can't tell whether it is really Jesus talking with me or whether it is just my imagination."

On

Using The Spiritual Exercises Explicitly

The first three sections of this manual contain many examples about the

more explicit use of the Exercises while guiding another on the Exercises

journey. These sections also include illustrations about this more explicit

use of the Exercises in other settings of spiritual direction.(28)

Section IV explores various connections between the explicit use of the

Exercises and other settings of ongoing spiritual direction. The scenarios

with Jean, Melinda, and Beverly above also illustrate the explicit use

of the Exercises in spiritual direction. Therefore, I will handle only

briefly the following question: In the setting of ongoing spiritual direction,

if a spiritual guide were to use the Exercises more explicitly, what features

would you notice?

In the questionnaire earlier in this chapter, the questions numbering six through nine represent the kind of questions that a guide might ask. I am taking for granted that many such themes might be introduced indirectly, not with direct questions. I used the question format there for the sake of clarity. In fact, most of the time, if you were a "fly on the wall," you would not notice much difference between such a spiritual director and one who does not use the Exercises at all!

However if you were to stay on that wall long enough, and if you were to reflect critically upon the various aspects of the way he was guiding his directee, you would notice that he:

a) Usually attends to his directee's specific interior experiences of prayer that actually took place within specific times of prayer. For example, if he were meeting with his directee only once a month, in addition to listening to her general experiences of her relationship with God in both life and prayer, he might expect her to tell him more specifically about three different prayer periods from the past month.(29) Spiritual directors from a more implicit approach or from other traditions of spirituality may invite their directees to talk in general about their relationship with God, but they would seldom invite their directees to talk specifically about their experiences from actual prayer times.One final comment: When a spiritual director uses the Exercises according to a more explicit mode in an appropriate manner, automatically he is also using other aspects of the spiritual direction model -- gospel values, theological insight, and faith -- in a more explicit mode.b) Suggests prayer methods and reflective skills from Exercises whenever they might be helpful. For example: Gospel Contemplation, Review, Repetition, Awareness Examen, etc. (Consult Chapter 31)

c) Explicitly uses, whenever relevant, the Guidelines for Discerning Spirits and their terminologies [313]-[336].

d) Frequently helps a directee, who has made the Exercises journey, to identify some of the events of her life experiences in terms of the content of the Exercises. He might ask something like:

e) Often discusses with his directee what grace she is needing at this time in her life; and, in the light of this discussion, together come up with some suggestions for praying with scripture to dispose her for this grace [1], [5]."In what ways does the event we have been talking about involve the Two Standards?" [136]-[147] or "In what ways might our Triune God regard that episode?" [102] or "How is your experience with your dying friend an expression of the Grace you prayed for during passion and death of Jesus in the Exercises journey?" [193] f) Discusses with his directee her operative theology [22].

g) Makes use of some of the dynamics and methods of the Exercises for discerning choices [169]-[189].

h) Primarily deals with those issues of life that surface within the directee's experiences of prayer.

i) Stresses the humanity of Jesus, the centrality of the cross, the importance of conscious decision-making, and the value of human activity and responsibility in companionship with God [91]-[98], [230]-[237].

j) Applies a key principle enunciated by Ignatius in the P & F to the Exercises themselves; namely, created things are to be used inasmuch as they help us to praise, reverence and serve God, and not used insofar as they hinder us from that goal [23]. Thus the Exercises are meant to be used only "... inasmuch as...."

Some material for your study, reflection, discussion .....

1. In the last statement, the qualification -- "in an appropriate manner" -- was made. Why?On Using Social Analysis

2. Using examples, explain why the explicit use of the Exercises in various spiritual direction settings even outside the Exercises journey automatically makes explicit the gospel, theological and faith dimensions of the model of spiritual direction.

In the presence of so much pluralism even in what seems to be a worldview common to both director and directee, it is important to recognize how our personal experiences are a product not only of the interface between our unique personal histories and our immediate situations but also of both obvious and not-so-obvious-underlying structures that make us feel the way we do. Here are some examples of how our own personal feelings and experiences are products of the systems in which we live:

- The disappointment and sadness a mother felt when she was not remembered on Mother's Day by her out-of-town daughter even though her daughter was with her a week and a half earlier;

- Feelings and experiences behind such expressions as,"I really have to learn to feel good about myself!" ... "I have to stop living up to other people's expectations!" .... "I did this for me!" ... "I need a safe place to worship";

- The fatigue of the principal of a small school when she is faced with writing and sending reports and surveys to an impersonal bureaucracy;

- The frustration of a church worker who experiences many of his initiatives frustrated by the pastor-in-charge;

- The feelings of failure of the unemployed male in a down-sized economy;

- The anger and guilt of the single or divorced person who is no longer invited to parties;

- The experiences of being put down for being a right-brained person in an institution that fosters left-brained activity.

As an example of this, let us take the scenario of an organist-choir master in a large, church-related, private school. Let us call him Jim. He is filled with anger and frustration over an experience of being verbally put down, dismissed, and trivialized by the principal. In this scenario, he has just told the spiritual director of this event. They spend the major part of this session on it.

Over the past two years, the spiritual director has become very familiar with Jim's background and now he explores the experience with Jim in the light of that knowledge. Indeed he can help Jim come to some deeper appreciation of that experience in terms of Jim's personal history. Jim was an adopted child who moved from one foster home to another. In their previous sessions together, the spiritual director helped Jim come to terms with his past, express his feelings, and develop strategies in dealing with his exaggerated need to seek approval along with his overly enthusiastic approach to belong.

However, if this spiritual director were to help Jim analyze the value structures of the educational institution to which he belongs and its attitudes towards music and art, they might discover together that, despite the school's professed theoretical support for Jim's work, there is, in practice, no support. Jim might begin to acknowledge that his job has very little value in the system in which he works and lives. He was, indeed, put down and devalued. His reactions and perceptions were quite accurate. They are not a skewed product of his past, but they are a faithful reflection of the present social structure in which he finds himself!

What

Is Social Analysis?

Social analysis originated in the Latin American context when ordinary

and disempowered people needed methods to gain power in oppressive situations.

Social analysis is done as a facilitated group process to understand the

social situation more completely in order to make important decisions for

group action. Social analysis helps to surface and get insight into the

data of the situation before decisions can be made about it.

When doing social analysis in such a group, everyone asks questions concerning the life situation that contributes to the continuing oppression or disempowerment that the community is experiencing. One question leads to another. Every person in the group, from the simplest peasant to the more educated leader, helps to uncover the underlying causes and structures through questions such as in the following simple social-analysis format.(30)

Steps For Social Analysis

Description Of The Situation With Its Different Aspects

1. Can you describe the situation?Explore Together Why Things Are This Way

2. What is humanizing/dehumanizing about it?

3. Who suffers?

4. Who gains?

5. What is the history of the situation?Explore Together What Can Or Should Be Done

6. Who benefit(s) from this situation? Who exercise(s) power and how is this power exercised? Who are in the in-group and who are the marginalizeded?

7. What role does money play in this situation?

8. What structure(s) support(s) the situation? What symbols or slogans make it right to keep the situation as it is?

9. What traditions and ways of thinking lie behind the particular difficulty encountered in this situation?

10. How does the wider culture with the economic system contribute to the situation?

11. What rules, roles, policies, mind-sets, and assumptions produce and reinforce the situation?

12. Is there a gap between the situation as it is and the situation as it ought to be?In the previous scenario with Jim, some of these same social-analysis questions could be employed by his spiritual director to help Jim deal with his situation in a Christian manner. Through the heightened awareness of the social and consequent mental structures involved in his situation, little by little Jim could be led to accept more of the truth of his situation. Later through a kind of reflection suggested below, he would be encouraged to reframe his experience in terms of its multi-dimensions and his faith. Through this approach, his own personal experience of the situation and his own anger are validated so that he can begin to deal with his situation in a Christian way. Not to acknowledge these structures is to begin with a lie which could devalue him even more.

13. If this situation remains, what will be the consequences for us? For others?

14. How would the situation be affected if we were to take another stance?

Some material for your study, reflection, discussion .....

1. If you were Jim's spiritual director and if you wanted to help him understand his experiences of being devalued in more than a psychological way, which of the social-analysis questions above might be appropriate to use?On Using Theological Reflection2. In what ways can social analysis be helpful for the work of spiritual direction in our present culture?